PRACTICE CHANGER

Stop using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for surgical procedures to “bridge” low- to moderate-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score ≤ 4) who are receiving warfarin. The risks outweigh the benefits.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single good-quality randomized controlled trial.1

CASE A 75-year-old man comes to your office for surgical clearance before right knee replacement surgery. He has diabetes and high blood pressure and is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. He is scheduled for surgery in a week. What is the safest way to manage his warfarin in the perioperative period?

More than 2 million people are being treated with oral anticoagulation in North America to prevent stroke or to prevent or treat venous thromboembolism.2 Since 2010, several new oral anticoagulants have been approved, including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban. These new medications have a shorter half-life than older anticoagulants, which enables them to be stopped one to two days before surgery.

On the other hand, warfarin—which remains a common choice for anticoagulation—has a three- to seven-day onset and elimination.3,4 This long clinical half-life presents a special challenge during the perioperative period. To reduce the risk for operative bleeding, the warfarin must be stopped days prior to the procedure, but clinicians often worry that this will increase the risk for arterial or venous thromboembolism, including stroke.

An estimated 250,000 patients need perioperative management of their anticoagulation each year.5 As the US population continues to age and the incidence of conditions requiring anticoagulation (particularly atrial fibrillation) increases, this number is only going to rise.6

Current guidelines on bridging. American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines recommend transition to “a short-acting anticoagulant, consisting of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin, for a 10- to 12-day period during interruption of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy.”5Furthermore, for an appropriate bridging regimen, the ACCP guidelines recommend stopping VKA therapy five days prior to the procedure and utilizing LMWH from within 24 to 48 hours of stopping VKA therapy until up to 24 hours before surgery.5 Postoperatively, VKA or LMWH therapy should be reinitiated within 24 hours and 24 to 72 hours, respectively, depending on the patient’s risk for bleeding during surgery.5

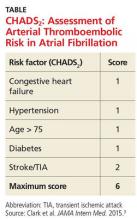

These guidelines recommend using CHADS2 scoring (see the table) to determine arterial thromboembolism (ATE) risk in atrial fibrillation.3,5 Patients at low risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-2) should not be bridged, and patients at high risk (CHADS2 score, 5-6) should always be bridged.5 These guidelines are less clear about bridging recommendations for patients considered to be at moderate risk (CHADS2 score, 3-4).

Previous evidence on bridging. A 2012 meta-analysis of 34 studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of perioperative bridging with heparin in patients receiving VKA.7Researchers found no difference in ATE events in eight studies that compared groups that received bridging vs groups that simply stopped anticoagulation (odds ratio [OR], 0.80).7 The group that received bridging had an increased risk for overall bleeding in 13 studies and of major bleeding in five studies.7This meta-analysis was limited by poor study quality and variation in the indication for VKA therapy.

A 2015 subgroup analysis of a larger cohort study of patients receiving anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation found an increased risk for bleeding when their anticoagulation was interrupted for procedures (OR for major bleeding, 3.84).8

Douketis et al1 conducted a randomized trial to clarify the need for and safety of bridging anticoagulation for ATE in patients with atrial fibrillation who were receiving warfarin.

Continue for study summary >>