MRI and CT often reveal thick nodular tissue in a largely hemorrhagic and/or necrotic osseous lesion, with an associated soft-tissue mass that allows distinction from an aneurysmal bone cyst.3 Next, patients generally undergo a nuclear medicine bone scan and CT of the chest to observe for signs of metastases. Chest CT is commonly repeated on a regular basis during and after treatment.9

Pathologic evaluation, the final step to diagnosis, is very important, especially in the effort to differentiate TOS from an aneurysmal bone cyst. The typical gross findings for a TOS tumor include a dominant cystic cavity–like architecture, with a pushing peripheral margin that frequently expands and erodes the adjacent cortex and extends into the surrounding tissue. There is usually no area of intramural bone tissue.

Microscopically, the cystic areas contain clots and fragments of tumor that are often lined with a layer of neoplasm. The blood-filled telangiectatic spaces form in these areas. The spaces are irregularly shaped and typically traversed by septae composed in part of neoplastic cells. Osteoid formation through these cells can appear as a fine, ice-like material between tumor cells.4,7

Treatment

The main goals of treatment are to limit the anatomical extent of the disease, decrease the possibility of recurrence, and restore the highest possible level of function.2 Initial treatment of any OS or TOS consists of aggressive, immediate chemotherapy prior to and after any surgical intervention.1 (Chemotherapy will not be discussed in further detail here.) Surgical treatments for patients younger than 14 include amputation (above the lesion with wide margins), an expanding prosthesis, or rotationplasty. The location and extent of the tumor, the patient’s age, and his or her desired lifestyle will all have an impact on the choice of surgery.10

Historic data demonstrate that patients who undergo amputation alone almost always develop metastatic disease.1 Other data show that only 10% of patients with OS have been cured by chemotherapy alone. Yet when medical treatment is combined with surgical treatment, the overall expected cure rate can be as high as 65%.2

Discussing amputation with a young patient and the family can be emotionally difficult. If functional levels are to be restored, above-knee amputation (AKA) is the least favored surgical method. Compared with healthy individuals, patients who undergo AKA will walk 43% less quickly and will expend much more energy. These patients frequently have an inefficient gait and, given their limited reserve, they may lose the ability to walk altogether.2

Reconstructive surgical options include limb-salvage procedures; since the late 1980s, these have become the standard of care for OS at all sites.11 One such option includes removal of the lesion (eg, a distal femoral or proximal tibial lesion) with acceptable margins and replacement of the lost bone with an allograft or with a metallic prosthesis and knee joint (called arthroplasty). This endoprosthesis expands as the child grows (by way of a minor surgical procedure or a magnetic spring) so there is no apparent discrepancy between limb lengths, and the patient’s appearance is as normal and socially acceptable as possible.1,2

Because the case patient developed a pathologic fracture through his TOS tumor, he was not a candidate for endoprosthesis. His options were AKA or rotationplasty.

This procedure was first described in 195012 for treatment of proximal focal femoral deficiency. It is considered an alternative for skeletally immature individuals for whom the goal is to preserve function.

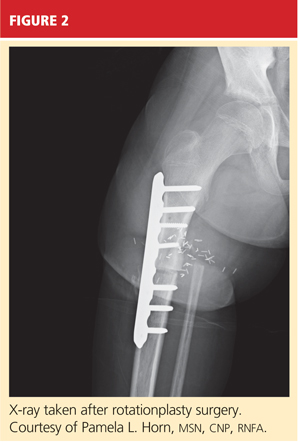

When AKA is indicated, the lower limb can be salvaged to allow functioning similar to that of a patient with a below-knee amputation (BKA). During rotationplasty, all but the most proximal aspect of the femur is resected. The tibia is externally rotated on the axis of the neurovascular bundle, then an arthrodesis of the proximal portion of the femur and the tibial plateau is performed (see Figure 2).

The end result is an extremity with the appearance, dimensions, and functional potential of a BKA. The ankle is rotated 180° so that it can serve as the new knee joint, and the attached foot, now pointing in the opposite direction, acts as the residual limb for fitting a prosthesis.2 This procedure is favored in patients with an extensive soft-tissue mass, intra-articular extension of the tumor, and/or pathologic fractures. It can also help prevent phantom pain.13

The Case Patient

After psychological evaluation of the patient and extensive family discussion, he underwent successful rotationplasty. The day after his surgery, however, he developed compartment syndrome and was required to undergo fasciotomies of the calf and proximal thigh. His wounds were treated, a skin graft was performed to close the proximal thigh wound, and his calf wounds were sutured closed (see Figures 3 and 4). His hip range of motion is excellent, and his ankle range of motion continues to improve with physical therapy.