A 45-year-old woman noticed some redness and scaling around her right nipple. She applied peroxide and OTC antibiotic ointment for approximately seven months with mixed results. She sought medical attention when pain developed in the breast, along with some bloody discharge from the nipple (see Figure 1). Around that time, she also noticed three small nodules in the upper outer portion of the breast.

A mammogram and ultrasound revealed a 1.7 × 2.0–cm spiculated mass in the axillary tail, as well as two smaller breast lesions. A PET/CT scan ordered subsequently revealed intense uptake in the periareolar region and a suspicious axillary node. By then, the biopsy results had confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma, later determined to be Paget’s disease of the breast (PDB).

The patient’s previous medical history was significant for cystic breasts (never biopsied), chronic back pain, anxiety, and obesity. She was perimenopausal with irregular periods, the last one about 10 months ago. Her obstetric history included two pregnancies resulting in live births and no history of abortion; her menarche occurred at age 14 and her first pregnancy at 27. Family history was significant for leukemia in her maternal grandmother and niece. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs. She lived at home with her husband and two daughters, who were all very supportive.

The patient elected to undergo a right modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and prophylactic left total mastectomy. MRM was performed on the right breast because sentinel lymph node identification was unsuccessful. This may have been due to involvement of the right subareolar plexus. Five of eight lymph nodes later tested positive for malignancy. The surgery was completed by placement of bilateral tissue expanders for eventual breast reconstruction.

Chemotherapy was started six weeks after surgery and included 15 weeks (five cycles) of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab (a combination known as TCH), followed by 51 weeks (17 cycles) of trastuzumab, along with daily tamoxifen. The TCH regimen was followed by four weekly cycles of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Adverse effects of treatment have included chest wall dermatitis, right upper extremity lymphedema, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, and fatigue.

Discussion

Nearly 150 years ago, James Paget recognized a connection between skin changes around the nipple and deeper lesions in the breast.1 The disease that Paget identified is defined as the presence of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma cells (ie, Paget’s cells) within the epidermis of the nipple, with or without an underlying carcinoma.

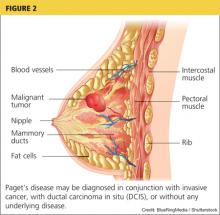

An underlying breast cancer is present 85% to 95% of the time but is palpable in only approximately 50% of cases (see Figure 2). However, 25% of the time there is neither a palpable mass nor a mammographic abnormality. In these cases particularly, timely diagnosis depends on recognition of suspicious nipple changes, followed by a prompt and thorough diagnostic workup. Unfortunately, the accurate diagnosis of Paget’s disease still takes an average of several months.2

Paget’s disease is rare; it represents only 1% to 3% of new cases of female breast cancer, or about 2,250 cases a year.2-4 (The number of Paget’s disease cases per year was calculated by the author, based on the reported incidence of all breast cancers.) It is even more rare among men. For both genders, the peak age for this disease is between 50 and 60.2

Paget’s disease is an important entity for primary care PAs and NPs because it presents an opportunity to make a timely and life-changing diagnosis, and because it provides an elegant model for understanding current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to breast cancer.

Clinical Presentation and Pathophysiology

The hallmark of PDB is scaly, vesicular, or ulcerated changes that begin in the nipple and spread to the areola. These changes are most often unilateral and may occur with pruritus, burning pain, and/or oozing from the nipple.5 This presentation is often mistaken for common skin conditions, such as eczema. Like eczema, changes in PDB may improve spontaneously and fluctuate over time, which is confusing for both the patient and clinician. A clinical pearl is that eczema is more likely to spread from the areola to the nipple, and will usually respond to topical corticosteroids. By contrast, changes in PDB tend to spread from the nipple to the areola, and corticosteroids do not provide a sustained response. Of note, Paget’s lesions may heal spontaneously even as the underlying malignancy progresses.6

PDB is unique because the underlying lesion and skin changes are not just coincidental. The cutaneous changes and the malignancy that lies beneath have a causal, not merely co-occurring, relationship. Paget himself believed that the nipple changes were both a precursor, and a promoter, of the underlying cancer.1 This transformation theory states that normal nipple epidermis turns into Paget’s cells spontaneously, before there is any underlying disease. This theory is supported by the fact that, occasionally (though rarely), no underlying breast cancer is ever found. Also, the concomitant tumor may be some distance (> 2 cm) from the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), suggesting a synchronous but causally unrelated lesion.6-8