Dr Takematsu is a senior fellow of medical toxicology, department of emergency medicine, New York University School of Medicine and New York City Poison Control Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at New York University School of Medicine and New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 50-year-old man with a 16-year history of injection heroin abuse presented to the ED complaining of ulcerative lesions on his right arm, which he stated had become worse over the past 3 months. He claimed the skin lesions, which involved his entire right arm, had grown “wider and deeper” since he started using the drug “Krokodil.” He further noted that he obtained the product from four different drug suppliers but did not know how it was prepared.

On presentation, his vital signs were: blood pressure, 135/78 mm Hg; heart rate, 92 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/minute; temperature, 98.2˚ F. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Physical examination of the right arm was notable for broad ulcers that exposed fat tissue and muscle and involved the entire forearm circumferentially (Figure 1). There were no signs of acute infection such as erythema, warmth, or abscess formation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

What is Krokodil?

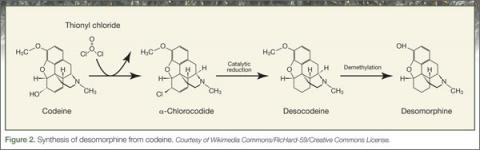

The name Krokodil is derived from the Russian word for crocodile, and stems from the greenish, severely damaged “crocodile-like” skin lesions purportedly caused by subcutaneous injection of this opioid derivative. Krokodil is not a specific drug but rather it describes the product derived from an attempt to synthesize desomorphine, the core ingredient. Desomorphine is a short-acting opioid analogue that has a reported potency eight to 10 times greater than morphine (Figure 2).

Also called “Russian Magic,” Krokodil has been used in Russia since 2003 following the country’s major restrictions on the importation of heroin. Since desomorphine can be synthesized from codeine, which was available in over-the-counter medications in Russia until 2012, drug users have turned to it as an inexpensive heroin substitute. (The average cost of a codeine-containing product is about 120 Rubles [$4.00] per 10-pack.1)

The chemical process of synthesizing desomorphine typically involves mixing one to five packs of codeine-based analgesics1 with a solvent (eg, paint thinner, gasoline), along with iodine and red phosphorous, which can be obtained from the striking pads of matchboxes.2 This produces a yield equivalent to 500 Rubles of heroin, making it an attractive alternative to low-income drug users.1 However, the yields are poor, and the starting products vary based on the codeine source. No systemic analysis of Krokodil has been performed to assess the purity and concentration of desomorphine in the resulting product.

What are the risks of using Krokodil?

Krokodil is typically self-administered by either intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (“skin-popping”) injection. Solvents and contaminants in the product can damage tissue with which they come into contact. Thus, IV use of this product causes venous scarring and collapse3; when venous access is exhausted, or following infiltration, the subcutaneous route may lead to necrosis and ulceration of the skin. These lesions are said to be used by illicit drug users as a “shooter’s patch” to inject drugs,4 leading to further skin damage. In addition to the local dermal effects, systemic inflammation results from the dissemination of the components of the product, causing neurological, solid-organ, and other effects.

Has Krokodil reached the United States?

Because of the horrifying appearance of the skin lesions, Krokodil has been called by many descriptive names such as the “flesh-eating drug” and “zombie-apocalypse drug,” which in turn has led to somewhat sensationalistic media reporting. There is, however, no clear evidence of entry of desomorphine or of Krokodil use in the United States, and most authorities feel either is unlikely to occur. This speculation is supported by the low cost and easy availability of heroin in the United States compared to Russia. Of note, although Russia banned the nonprescription sale of products containing codeine in November 2012, the ban has had minimal impact on the rate of necrotic skin lesions.

To date, none of the so-called cases of Krokodil-associated lesions reported in the United States have confirmatory analytical testing, and diagnoses have been based primarily on history or morphological features of the wound. Furthermore, no reference laboratories in the United States have identified desomorphine in any of their tested samples. Since the skin lesions are not pathognomonic of Krokodil use and share morphologic features with all forms of subcutaneous drug use, analytical confirmation is critical to identifying this as an emerging drug trend. Therefore, users of product sold or brewed as Krokodil may develop skin lesions regardless of desomorphine content due to contaminants in the injected product.