Public health officials in El Paso, Texas, reported in September 2014 that more than 850 infants and 43 health care workers (HCW) at Providence Memorial Hospital may have been exposed to tuberculosis (TB) by a nurse with active infection. In collaboration with the CDC, the hospital administrators and local and state health officials advised potentially exposed individuals and their families to be screened for TB. According to press reports, five infants tested positive for TB and were to be treated.1,2 This news report highlights the importance of maintaining infection control protocols in health care facilities throughout the United States to reduce the risk for TB transmission.

SCREENING HEALTH CARE WORKERS

In the US, reported cases of TB, a treatable and curable disease, have declined since 1993. A total of 9,582 cases were reported in 2013, with 536 deaths due to TB reported in 2011 (the most recent year for which this data is available).3

Even though TB is on the decline worldwide,4 HCWs remain at increased risk for infection, confirming that TB is an occupational disease.5 It is imperative that health care facilities have effective infection control plans in place, primarily to reduce the risk for transmission of TB to HCWs.

This article reviews the available TB screening tests, CDC recommendations, parameters for evaluating test performance, and recent studies that lend support to the superiority of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release assays (IGRAs) over tuberculin skin tests (TSTs) as part of HCW screening and infection control for TB. Primary care clinicians need to know about the status of these tests not only because we are HCWs ourselves, but because we are often responsible for the safety of other HCWs in our workplaces.

TB SCREENING TESTS

Diagnosing latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is key to overall control of the disease, since treatment decreases risk for conversion to active disease. Until recently, the diagnosis of LTBI relied on the TST, despite its limitations (see discussion under “Accuracy”). Now, immune-based blood tests hold promise for improving LTBI diagnosis.

Tuberculin skin test

In 1934, Florence Seibert developed what is known today as the purified protein derivative (PPD) test, which was adopted as the standard in the US in 1941.6 For 60 years, the PPD TST was the only screening method for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. It involves the intradermal injection of PPD; a hypersensitivity response leads to a cutaneous induration at the injection site after 48 to 72 hours.7Hence, the TST is a two-step test, requiring a follow-up visit for the result to be read.

Although strongly predictive of TB, the TST may result in false-positive test results in those previously immunized with the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine (a WHO-recommended childhood vaccination against TB, widely used outside the US),8 and in those exposed to certain nontuberculous mycobacteria such as M bovis and M africana.9 Test results may also be false negative in immunocompromised patients.9

Interferon-γ release assays

With the goal of developing a more specific and sensitive test for TB infection, IGRAs were developed in the mid-1990s as a new tool to detect active and latent TB infection.10 The first IGRA test for TB received FDA approval in 2001.11 There are currently two FDA-approved IGRAs—QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and T-SPOT.TB—in use.

QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test. The QFT-GIT measures cell-mediated immune responses to antigens that simulate mycobacterial proteins. Requiring only one patient visit, whole blood is collected in three different tubes (negative control, TB antigen, and mitogen [positive] control), each containing a single antigen.12 After 16 to 24 hours in a temperature-controlled environment, the tubes are centrifuged to separate the plasma. IFN-γ levels are measured in each tube to calculate the test result.

T-SPOT.TB test. Using one blood sample, the T-SPOT.TB test captures IFN-γ produced by activated T-cells in response to stimulation by two M tuberculosis antigens. Addition of a substrate produces dark blue spots; the number of spots indicates the quantity of M tuberculosis-sensitive effector T-cells in the peripheral blood. A positive result is eight or more spots; a negative result is fewer than four spots, and a borderline result is five to seven spots.13 Unlike the QFT-GIT, the T-SPOT.TB has a “borderline” interpretation category.

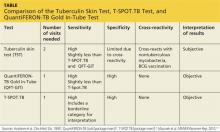

See the Table for a comparison of the TST, QFT-GIT, and T-SPOT.TB tests for TB screening.

Continue for CDC guidelines >>