› Consider recommending medical marijuana for conditions with evidence supporting its use only after other treatment options have been exhausted. B

› Thoroughly screen potential candidates for medical marijuana to rule out a history of substance abuse, mental illness, and other contraindications. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Gladys B, a 68-year-old patient with a history of peripheral neuropathy related to chemotherapy she underwent years ago, has been treated alternately with acetaminophen with codeine, tramadol, gabapentin, and morphine. Each provided only minimal relief. Your state recently legalized medical marijuana, and she wants to know whether it might alleviate her pain.

If Ms. B were your patient, how would you respond?

Medical marijuana is now legal in 23 states and Washington, DC. Other states are considering legalization or have authorized particular components for use as medical treatment.1 As such laws proliferate and garner more media attention, it is increasingly likely that patients will turn to their primary care physicians with questions about the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes. What can you tell them?

Conversations about medical marijuana should be based on the understanding that while many claims have been made about the therapeutic effects of marijuana, only a few of these claims have evidence to back them up. Major medical organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians,2 the American College of Physicians,3 and the Institute of Medicine,4 recognize its potential as a treatment for various conditions, but emphasize the need for additional research rather than wholesale adoption.

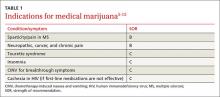

Most commonly, medical marijuana is used to treat pain symptoms, but it is also used for a host of other conditions. A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis5 found moderate-quality evidence to support its use for the treatment of chronic and neuropathic pain and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), and low-quality evidence for the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, for weight gain in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and to treat Tourette syndrome. (TABLE 1 lists the conditions for which medical marijuana has been found to be indicated.5-13) For most other conditions that qualify for the use of medical marijuana under state laws, however—insomnia, hepatitis C, Crohn’s disease, and anxiety and depression, among others—the evidence is either of very low quality or nonexistent.5

Evaluating marijuana is difficult

It is important to note that marijuana comprises more than 60 pharmacologically active cannabinoids, which makes it difficult to study. Both exogenous ligands, such as the cannabinoids from marijuana, and endogenous ligands (endocannabinoids), such as anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, act on cannabinoid receptors. These receptors are found throughout the body, but are primarily in the brain and spinal cord.14

The main cannabinoids contained in marijuana are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC produces the euphoria for which recreational marijuana is known, but can also induce psychosis. CBD is not psychoactive and is thought to have antianxiety and possibly antipsychotic properties. Thus, marijuana’s therapeutic effects depend on the concentration of THC in a given formulation. Because CBD has the ability to mitigate psychoactive effects, the ratio of THC to CBD is important, as well.15

What’s more, medical marijuana is available in various forms. It can be smoked—the most widely used route—or inhaled with an inhalation device, ingested in food or as a tea, taken orally, administered via an oromucosal spray, or even applied topically. Medical marijuana may be extracted naturally from the cannabis plant, produced by the isomerization of CBD, manufactured synthetically, or provided as an herbal formulation.

There are also cannabinoids that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—dronabinol (a synthetic version of THC) and nabilone (a synthetic cannabinoid). Nabiximols, a cannabis extract in the form of an oromucosal spray, is licensed in the UK for the treatment of symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis, but has not yet received FDA approval.16,17

As with any treatment or medication, the benefits must be weighed against the risks. Scientific studies have documented many adverse health effects associated with marijuana, including the risk of addiction and the potential for marijuana to be used as a gateway drug; its effect on brain development, school performance, and lifetime achievement; a potential relationship to mental illness; and the risk of cancer and motor vehicle accidents.1,16,18 Patients in clinical trials have reported dizziness, dysphoria, hallucinations, and paranoia, as well.12