The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus

The modern management of diabetes mellitus (DM) began with the discovery of insulin by Banting and Best in 1921 (see The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus in this supplement). Since that time, numerous additional classes of glucose-lowering agents have been introduced for the treatment of type 2 DM (T2DM). These medications primarily act by addressing 2 of the key defects of T2DM, insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. T2DM is a progressive disease process that requires continued adjustment of therapy to maintain treatment goals. Most patients with T2DM will require insulin therapy at some point in their lives.

Role of Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management

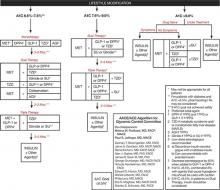

Consensus guidelines developed by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) recommend initiating insulin when oral therapy fails to achieve glycemic control, A1C > 9.0% in treatment-naïve patients, or if the patient is symptomatic with glucose toxicity (polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss) (FIGURE 1).1

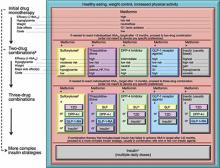

Similar consensus guidelines developed by the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) advise the initiation of glucose-lowering therapy for most patients with T2DM with the combination of lifestyle modifications, diet, and metformin (FIGURE 2).2 For patients who do not achieve or maintain glycemic control over 3 months, or thereabouts, with metformin, a second oral agent should be added. Alternatives include a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist or basal insulin. Insulin should be strongly considered as initial therapy for a patient with significant symptoms of hyperglycemia and/or plasma glucose >300-350 mg/dL or A1C ≥10.0%.

The major role of insulin in the management of patients with T2DM stems from several important attributes. First, insulin is the only treatment that works in patients with advanced β-cell deficiency. It acts directly on tissues to regulate glucose homeostasis, unlike other glucose-lowering agents that require the presence of sufficient endogenous insulin to exert their effects as insulin sensitizers, secretagogues, incretin mimetics, amylin analogs, and other factors. This also means that the mechanism of action of insulin is complementary to those of other glucose-lowering agents. Second, there is less of a ceiling effect with insulin. That is, increasing the dose of insulin results in a progressive lowering of blood glucose in the majority of patients, with the major limitation being the risk for hypoglycemia. Third, the glucose-lowering efficacy of insulin is durable, unlike that of other glucose-lowering agents that depend on endogenous insulin secretion for continued effectiveness. Fourth, insulin improves the lipid profile, particularly triglyceride levels.2-5 Fifth, regarding the long-term safety and tolerability of insulin, it is well established that weight gain, likely mediated via reduction of glycosuria, and hypoglycemia are typically the most concerning adverse events encountered. Allergic reactions, which were a more common complication of animal-sourced insulins, are infrequent with the insulin analogs.6-17 Finally, the availability of insulin in different formulations allows for targeting fasting plasma glucose or postprandial glucose, and individualization of therapy (see The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus in this supplement.)

While both the AACE/ACE and ADA/EASD consensus guidelines provide treatment “algorithms,” both make it clear that these are suggested approaches suitable for the population with T2DM (FIGURE 1, FIGURE 2). The specific treatment approach must be individualized based on patient-specific factors such as age, comorbid conditions, and tolerance of hypoglycemia.

FIGURE 1

Role of insulin in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to the AACE/ACE1

AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACE, American College of Endocrinology; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP4, dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitor; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GLP-1, glucagon–like peptide-1 agonist; MET, metformin; PPG, postprandial glucose; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Reprinted from American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE/ACE Diabetes Algorithm for Glycemic Control. Available at https://www.aace.com/sites/default/files/GlycemicControlAlgorithmPPT.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2012, with permission from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

FIGURE 2

Role of insulin in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to the ADA/EASD2

Moving from the top to the bottom of the figure, potential sequences of antihyperglycemic therapy. In most patients, begin with lifestyle changes; metformin monotherapy is added at, or soon after, diagnosis (unless there are explicit contraindications). If the HbA1c target is not achieved after ~3 months, consider 1 of the 5 treatment options combined with metformin: an SU, TZD, DPP-4-i, GLP-1-RA, or basal insulin. (The order in the chart is determined by historical introduction and route of administration and is not meant to denote any specific preference.) Choice is based on patient and drug characteristics, with the over-riding goal of improving glycemic control while minimizing side effects. Shared decision making with the patient may help in the selection of therapeutic options. The figure displays drugs commonly used both in the United States and/or Europe. Rapid-acting secretagogues (meglitinides) may be used in place of SUs. Other drugs not shown (α-glucosidase inhibitors, colesevelam, dopamine agonists, pramlintide) may be used where available in selected patients but have modest efficacy and/or limiting side effects. In patients intolerant of, or with contraindications for, metformin, select initial drug from other classes depicted and proceed accordingly. In this circumstance, while published trials are generally lacking, it is reasonable to consider 3-drug combinations other than metformin. Insulin is likely to be more effective than most other agents as a third-line therapy, especially when HbA1c is very high (eg, ≥ 9.0%). The therapeutic regimen should include some basal insulin before moving to more complex insulin strategies. Dashed arrow line on the left-hand side of the figure denotes the option of a more rapid progression from a 2-drug combination directly to multiple daily insulin doses, in those patients with severe hyperglycemia (eg, HbA1c, ≥ 10.0–12.0%).