Although it is often taken for granted, the ability to initiate and maintain sleep throughout the night is elusive for many. About one-third of adults experience a troublesome episode of insomnia.1 In most, it is transient, but in 10% to 15% (roughly 30 million people), the problem becomes self-perpetuating and chronic.2 Chronic insomnia is one of the most prevalent conditions that family physicians (FPs) encounter, a function of it being so closely associated with comorbid conditions that FPs deal with every day, such as depression, chronic pain, and polypharmacy.3,4

Insomnia can be vexing for a number of reasons. Because it is not acutely dangerous, patients may present it as an “add-on” concern at the end of an already lengthy visit. And because insomnia is often a symptom of multiple underlying physiologic and psychological factors, it requires the FP to engage in a thorough and time-consuming exploration of possible causes and comorbidities. Finally, standard treatment options have drawbacks: reports show that use of pharmacotherapy is troubling to prescribers primarily because of concerns about adverse effects and dependence;5-7 the other major therapeutic avenue, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), requires training and is time-consuming to deliver in the context of an office visit.8,9

Despite these obstacles, successful evaluation and treatment of insomnia can be highly rewarding. Chronic insomnia is associated with great individual misery and negative consequences for long-term health. Specifically, it is associated with reduced quality of life and daytime functioning,10 depression,11,12 hypertension,13,14 increased workplace accidents and absenteeism,15-17 and exacerbations of chronic pain.18 And while the evaluation and management of insomnia can be laborious, a systematic method can streamline the process.

Insomnia: Symptom or cause?

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders defines chronic insomnia as an inability to sleep sufficiently despite creating adequate opportunity. It occurs at least 3 nights per week for >3 months with perceived negative consequences during the day. Patients typically complain about symptoms including fatigue, diminished cognitive performance, and mood disturbance.19 Acute insomnia triggered by one or more biopsychosocial stresses is, by definition, self-limited and has different underlying mechanisms. As such, it will not be described in this review.

The chief risk factors are female gender, low socioeconomic status, and increasing age.20 However, cohorts of healthy seniors show preserved good sleep; the increase in prevalence of insomnia in the elderly is likely linked more specifically to age-related accumulation of medical/mental health disorders and polypharmacy than aging per se.21

In the past, insomnia was viewed as a symptom, occurring secondarily to an underlying cause, usually an acute biopsychosocial stressor or depression. It was assumed that if the primary cause was effectively treated, then healthy sleep would return.

But research over the past 20 years has changed this paradigm in 2 ways. First, when comorbidities such as depression or chronic pain are present, they have a bidirectional relationship with insomnia rather than a one-way cause and effect. For example, instead of depression being a primary disorder from which insomnia can result, it is now recognized that insomnia can be present first and is a risk factor for new-onset depression. When depression and insomnia coexist, they may exacerbate each other in a bidirectional pattern.

Secondly, an estimated 15% of chronic insomnia sufferers have no targetable comorbidity; rather, they are unable to get sufficient sleep in large part because of a trait-like predisposition to fragile sleep, called hyperarousal brain physiology.22 These people used to be described as having “primary insomnia,” although the term has been dropped from the 5th edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).23

Assess comorbidities, obtain sleep logs

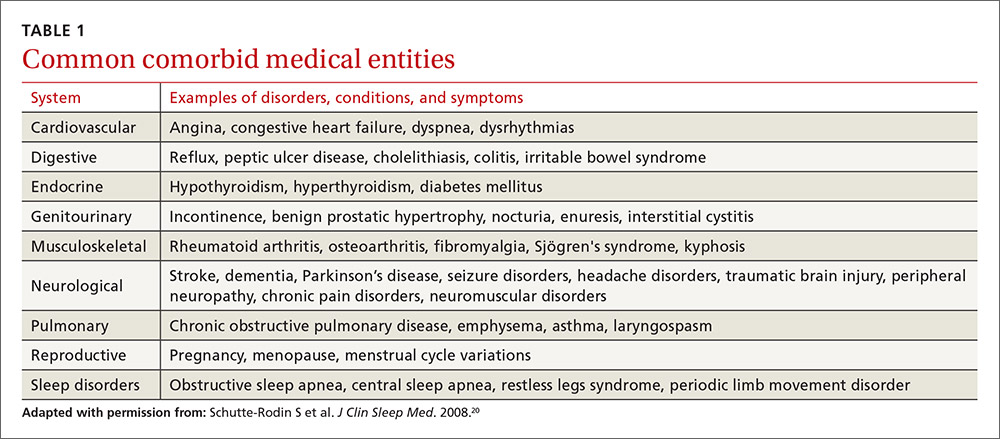

The evaluation of the chronic form of insomnia should begin with a thorough medical history to assess for comorbid conditions that can exacerbate disturbed sleep. These are generally grouped into medical disorders (TABLE 120), medications/substances (eg, antidepressants, stimulants, decongestants, narcotic analgesics, cardiovascular drugs, pulmonary agents, alcohol), and mental health disorders (especially depression and anxiety). It’s important to consider whether such comorbidities are contributing to the insomnia and optimize treatment that addresses them.

Take particular care to evaluate signs and symptoms of comorbid primary sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome (RLS), and circadian rhythm disorders since any of these can present with a complaint of insomnia. RLS, usually classified as a sleep disorder because of its circadian pattern (it is experienced more at night than during the day), is present to a troublesome degree in about 3% to 4% of all adults.24 It is important to inquire about symptoms of RLS (urge to move legs in the night more than during the day; relieved with movement; worsened with inactivity) so as not to miss this treatable cause of insomnia.

The physical exam should focus on signs that suggest sleep-disordered breathing—obesity, large neck girth, hypertension, and crowded oropharynx—because people with sleep apnea often present with the complaint of frequent awakenings.