CASE › Amber S,* a 33-year-old woman who works on the production line at a bread factory, sought care at my health center with a several month history of non-bloody diarrhea that was increasing in frequency and urgency and was accompanied by painful abdominal bloating and cramping. She said that these symptoms were negatively impacting her interpersonal relationships, as well as her productivity at work. She reported that “almost everything” she ate upset her stomach and “goes right through her,” including fruits, vegetables, and meat, as well as greasy fast food. She had researched her symptoms on the Internet and was worried that she might have something serious like inflammatory bowel disease or cancer.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) that negatively impacts the quality of life (QOL) of millions of people worldwide.1 In fact, one study of 179 people with IBS found that 76% of survey respondents reported some degree of IBS-related impairment in at least 5 domains of daily life: daily activities, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, symptom severity, QOL, and symptom-specific cognitive affective factors related to IBS.2

Estimating prevalence and incidence is a formidable challenge given various diagnostic criteria, the influence of population selection, inclusion or exclusion of non-GI comorbidities, and various cultural influences.3 That said, it’s estimated that IBS impacts approximately 11% of the world’s population, and approximately 30% of these individuals seek treatment.1,4 While there are no significant differences in GI symptoms between those who consult physicians and those who do not, those who do seek treatment report higher pain scores, greater levels of anxiety, and a greater reduction in QOL.5

All ages affected. IBS has been reported in patients of all ages, including children and the elderly, with no definable difference reported in the frequency of subtypes (diarrhea- or constipation-predominant).

This article reviews the latest explanations, diagnostic criteria, and treatment guidelines for this challenging condition so that you can offer your patients confident care without needless testing or referral.

A lack of consensus among practicing physicians

Historically, IBS has been regarded by many primary care physicians (PCPs) as a diagnosis of exclusion. Lab tests would be ordered, nothing significant would be found, and the patient would be referred to the gastroenterologist for a definitive diagnosis.

Perceptions and misconceptions about IBS continue to abound to this day. Many are neither completely right nor wrong partly because so many triggers for IBS exist and partly because of the heretofore lack of simple, standardized criteria to diagnose the condition. Other factors contributing to the confusion are that the diagnosis of IBS is purely symptom-based and that proposals of its pathophysiology have traditionally been complex.

For example, a 2006 survey-based study of PCPs and gastroenterologists found that PCPs were less likely than gastroenterologists to believe that IBS was related to prior physical or sexual abuse, previous infection, or learned behavior, but were more likely to associate dietary factors or a linkable genetic etiology with IBS.6 Both sets of beliefs, however, may be considered correct.

Similarly, a 2009 qualitative study conducted in the Netherlands found that general practitioners (GPs) considered smoking, caffeine, diet, “hasty lifestyle,” and lack of exercise as potential triggers for IBS symptoms, while PCPs in the United Kingdom considered diet, infection, and travel to be possible triggers.7 Again, all play a role.

While GPs reported that patients should take responsibility for managing their IBS and for minimizing its impact on their daily lives, they admitted limited awareness of the extent to which IBS affected their patients’ daily living.7

A 2013 survey-based study in England determined that GPs understand the relationship between IBS and psychological symptoms including anxiety and stress, and posited that the majority of patients could be managed within primary care without referral for psychological interventions.8 Moreover, they reported that a dedicated risk assessment tool for patients with IBS would be helpful to stratify severity of disease. The study concluded that the reluctance of GPs to refer patients for evidence-based psychological treatments may prevent them from obtaining appropriate services and care.

Newer explanatory model shines light on IBS

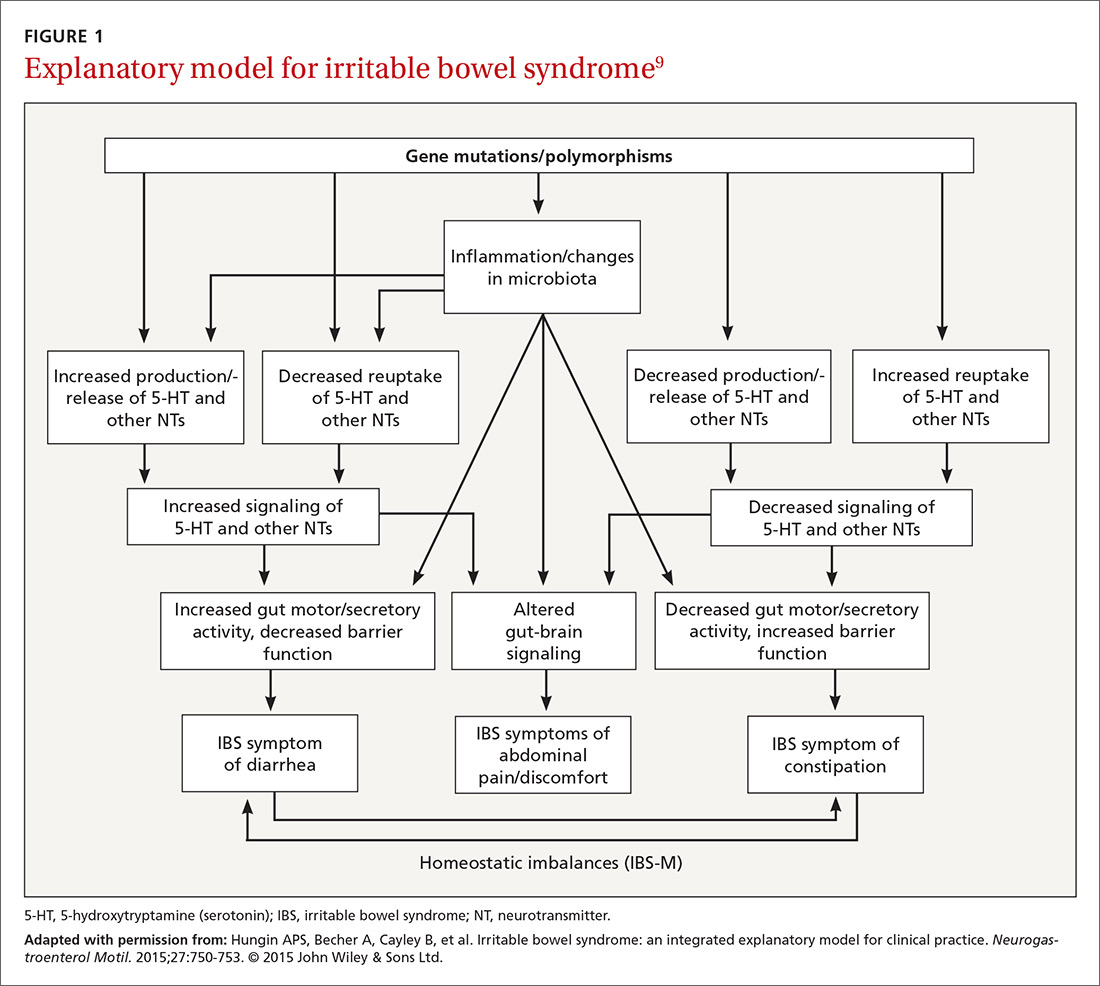

A newer explanation that is based on 3 main hypotheses is elucidating the true nature of IBS and providing a pragmatic model for the clinical setting (FIGURE 1).9 According to the model, IBS entails the following 3 elements, which combined lead to the symptoms of IBS:

- Altered or abnormal peripheral regulation of gut function (including sensory and secretory mechanisms)

- Altered brain-gut signaling (including visceral hypersensitivity)

- Psychological distress.