More than one-third of American adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 19 years are obese.1,2 Poor diet coupled with a sedentary lifestyle is the highest ranked cause of non-communicable disease and a leading cause of preventable death, according to the National Research Council.3

Bariatric surgery (BS) is a viable therapeutic option for obese patients who do not respond to conventional lifestyle interventions for losing weight. There are multiple gastrointestinal (GI) procedures available that are classified as either malabsorptive (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [RYGB] and biliopancreatic diversion [BPD] with or without duodenal switch) or restrictive (laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding [LAGB] and vertical sleeve gastrectomy [VSG]).

Approximately half of the 196,000 bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2015 were of the sleeve variety, another 23% were RYGB, and the remaining percentage was divided among the other types.4 Postoperative risks include nutritional deficiencies, decreased bone mineral density (BMD), dumping syndrome (when food rapidly dumps from the stomach to the intestine), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with possible ulceration.

Despite these potential complications, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that obese people who underwent BS (gastric banding or gastric bypass) had significantly reduced risks of global, non-cardiovascular (CV), and CV mortality compared with obese controls.5 Helping patients to realize these benefits requires that the entire health care team—especially the family physician—is aware of the special considerations for this population.

To that end, this article reviews the details of diagnosing and managing post-surgical complications. It also addresses issues unique to managing certain subpopulations, such as post-BS patients who require revision surgery or who want to pursue body contouring surgery; adolescents who undergo BS surgery; and women who want to get pregnant postoperatively.

Monitor patients for these post-surgery complications

Postoperative BS follow-up varies depending on location, surgeon preference, and availability of multidisciplinary resources. At our institution, patients have a minimum of 3 follow-up visits with their surgeon (during hospitalization and 2 weeks and 2 months postoperatively). This is followed by visits with Endocrinology 6 months after surgery and annually thereafter. Given the variability of follow-up, family physicians should coordinate with specialists where appropriate and be aware of postoperative complications and monitoring since it is likely they will have the most frequent contact with these patients.

Nutritional deficiencies are common and require lifelong screening

Nutritional deficiencies are the most common complications of malabsorptive BS. Guidelines from the Endocrine Society, as well as guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), The Obesity Society (TOS), and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), recommend routine lifetime screening for deficiencies after surgery.6,7 Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, and liver function tests should be obtained at one, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months following surgery and annually thereafter.6

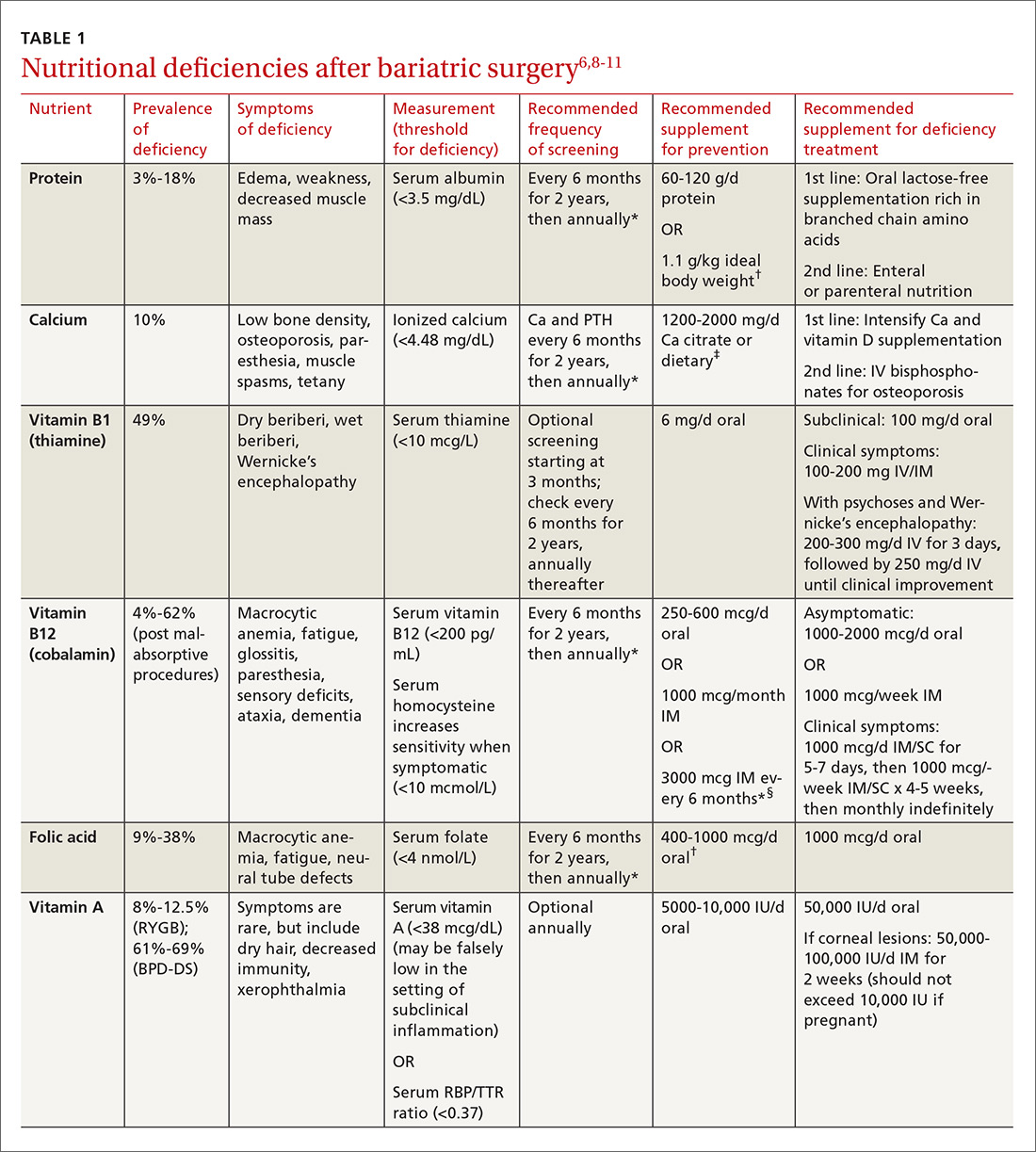

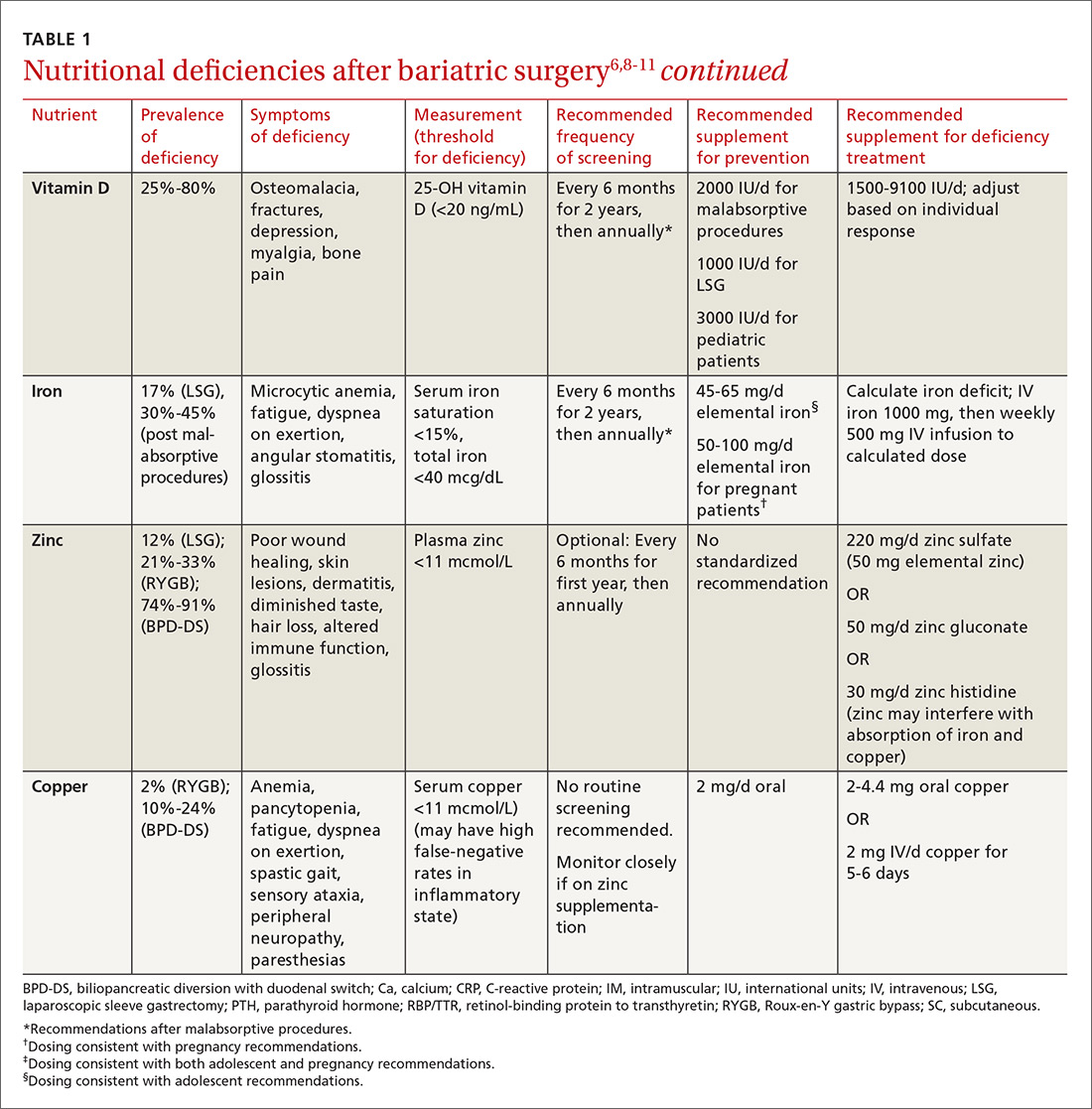

Multiple factors contribute to nutritional and micronutrient deficiencies, including reduced oral intake of food, decreased GI absorption, food intolerance, nausea/vomiting, and nonadherence with dietary supplements.8 Oral supplementation should be in chewable, powder, or liquid form because pill and capsule absorption may be altered.8,9 Over-the-counter multivitamins may not contain the requisite daily doses recommended after BS.9 Patients and physicians should evaluate supplements together to ensure appropriate nutritional and micronutrient supplementation (TABLE 16,8-11).

Bone mineral density can start to decrease soon after surgery

Studies evaluating BMD after BS have produced variable findings. In obese patients, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) measurements may not be accurate due to adipose tissue artifact and table weight limits. In addition, limited data exist on the incidence of fractures after BS. Of 2 notable studies, only one, a population-based study involving 258 Minnesota residents who underwent a first bariatric surgery between 1985 and 2004, demonstrated a significantly increased incidence of fractures.12,13

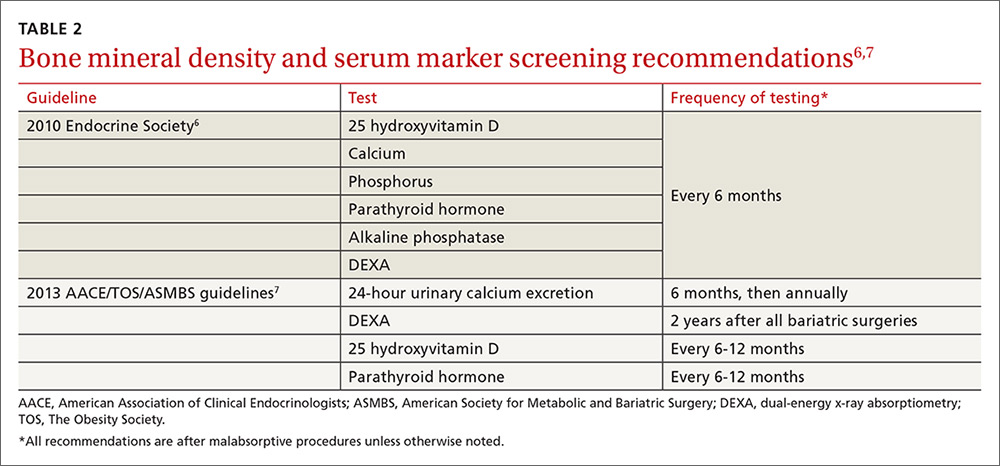

In addition, studies show bone turnover markers, including C-terminal telopeptide, increase as early as 3 months after BS.14 Several guidelines recommend routine BMD screening after BS (TABLE 2).6,7 The mechanism of bone demineralization is likely multifactorial—a function of the magnitude of the weight loss and skeletal unloading, calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, and associated secondary hyperparathyroidism.15 Treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism is adequate supplementation with vitamin D and calcium.

Optimal dosing for vitamin D has not been determined. One recent systematic review suggests routine prophylaxis with at least 2000 international units (IU)/d and found the greatest improvement for known deficiency with doses of 1500-9100 IU/d following malabsorptive surgeries.11 After laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, at least 1000 IU/d vitamin D is recommended.11

Overall, high variability exists among patients, and an individualized approach for dosing is recommended.11 Vitamin D levels should be monitored 2 and 4 weeks after initiation of treatment and every 3 months thereafter.11 Normal levels of serum calcium, 25-OH vitamin D, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, and 24-hour urinary calcium excretion indicate adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation.6