Presentation. Patients generally present with ankle pain, swelling, instability, pain when walking on uneven terrain, and pain upon push-off.9

Examination reveals reduced passive ankle dorsiflexion and tenderness upon palpation of individual ligaments. Several clinical tests have been described to aid in detecting this often-elusive diagnosis7,9,10,11:

- Squeeze test. The patient sits with the knee on the affected side bent at a 90° degree angle while the examiner applies compression, with one or both hands, to the tibia and fibula at midcalf. The test is positive when pain is elicited at the level of the syndesmosis just above the ankle joint.9,11

- External rotation test. External rotation of the foot and ankle relative to the tibia reproduces pain.

- Crossed leg test. The affected ankle is crossed over the opposite knee in a figure-4 position. The test is positive when pain is elicited at the syndesmosis.10

- Cotton test. The proximal lower leg is steadied with 1 hand and the plantar heel grasped with the other hand. Pain when the heel is externally rotated (and radiographic widening of the syndesmosis under fluoroscopy) signal syndesmotic instability.

- Fibular translation test. When anterior or posterior drawer force is applied to the fibula, pain and increased translation of the fibula (compared to the contralateral side) suggest instability.

With the Cotton and fibular translation tests, interexaminer technique is more variable and findings are less reproducible.8 Taken alone, none of the above-listed tests are diagnostic; they can, however, assist in making a diagnosis of an injury to the syndesmosis.11

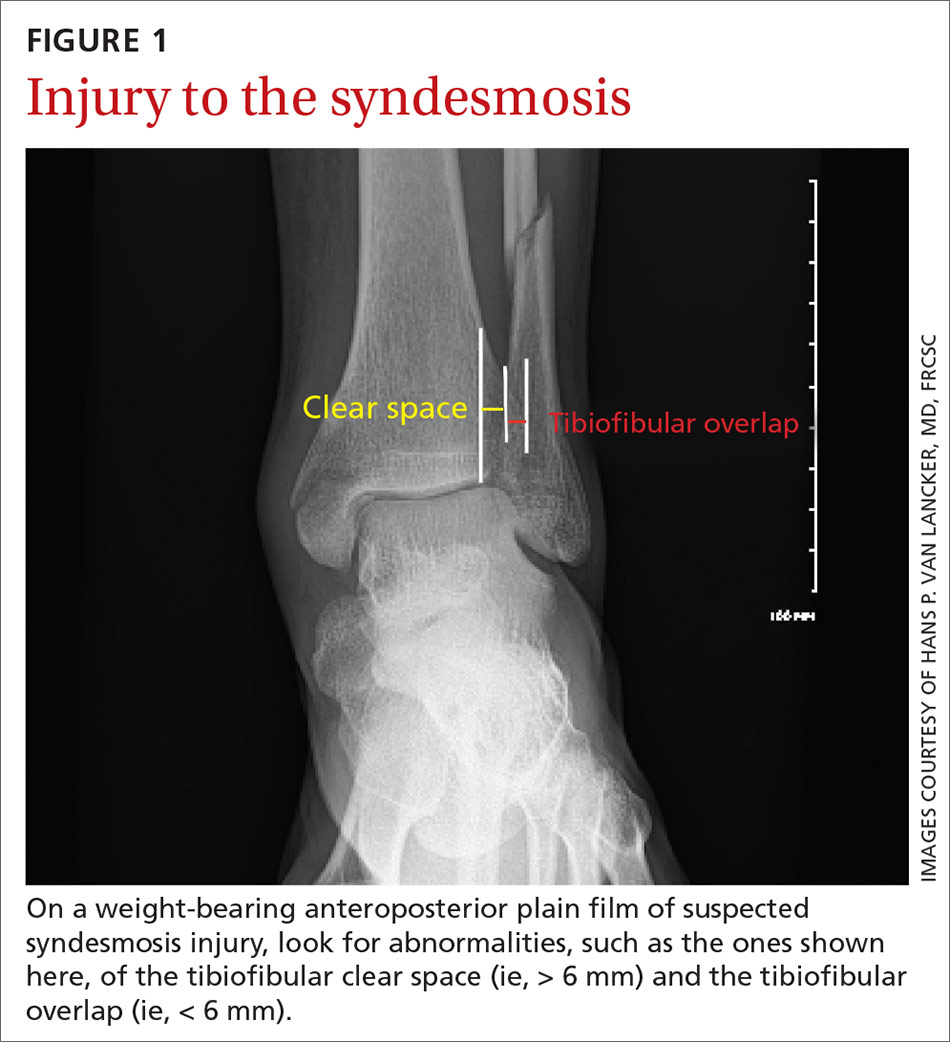

Imaging typically involves anteroposterior [AP], lateral, and mortise plain films of the ankle and weight-bearing AP and lateral views of the tibia and fibula.9 Important measures on weight-bearing AP x-rays are the tibiofibular clear space (abnormal, > 6 mm) and the tibiofibular overlap (abnormal, < 6 mm) (both abnormalities shown in FIGURE 1). Comparing films of the affected ankle with views of the contralateral ankle is often useful.

Management of syndesmotic injuries depends on degree of disruption:

- Grade 1 injury is a sprain without diastasis on imaging. Management is conservative, with immobilization in a splint or boot for 1 to 3 weeks, followed by functional rehabilitation over 3 to 6 weeks.10

- Grade 2 injury is demonstrated by diastasis on a stress radiograph. Although evidence to guide successful identification of a grade 2 injury is lacking, it is clinically important to make that identification because these injuries might require surgical intervention, due to instability. Because the diagnosis of this injury can be challenging in primary care, high clinical suspicion of a grade 2 injury makes it appropriate to defer further evaluation to an orthopedic surgeon. On the other hand, if suspicion of a grade 2 injury is low, a trial of conservative management, with weekly clinical assessment, can be considered. A diagnosis of grade 2 injury can be inferred when a patient is unable to perform a single-leg hop after 3 weeks of immobilization; referral to an orthopedic surgeon is then indicated.12

- Grade 3 injury is frank separation at the distal tibiofibular joint that is detectable on a routine plain film. Management—surgical intervention to address instability—is often provided concurrently with the treatment for a Danis-Weber B or C fracture, which tends to coexist with grade 3 syndesmotic injury. (The Danis-Weber A–B–C classification of lateral ankle fracture will be discussed in a bit.)

Continue to: Ankle fracture