Thanks to Dr. Linn et al for “Tips and tools for safe opioid prescribing” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:280-292), which addressed an important topic: the risks of, and poor evidence for, chronic opioids in noncancer pain.

Pain management is challenging, and it is easy to prescribe opioids from a desire to help. However, we must translate the evidence of chronic opioids’ poor benefit and real harms into practice. No studies show a long-term benefit of opioids for chronic noncancer pain, but they do demonstrate abundant findings of harm. As a family medicine community, we should be practicing at the highest level of evidence and addressing legacy opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain.

Increasing opioid doses for pain only offers short-term benefits and can result in rapid tolerance and withdrawal. We should not be starting people on opioids for knee and back pain. We do not need more ways to initiate opioids or tables on how to dose long-acting opioids—drugs that increase mortality.1 Let’s stop using poorly validated tools like DIRE to ignore the evidence against opioids (validated with 61 retrospective chart reviews; 81% sensitivity, 76% specificity for predicting efficacy of opioids).2,3

A 2018 randomized controlled trial of 240 patients with back, knee, or hip osteoarthritis found opioids were not superior to nonopioid medication for pain-related function at 12 months and had more adverse effects.4 A 2015 systematic review concluded there was insufficient evidence of long-term benefits of opioids but a dose-dependent risk of serious harm.5 Just 1 year of taking low-dose opioids can increase the risk of opioid use disorder by 0.7%, compared with 0.004% with no opioids.5

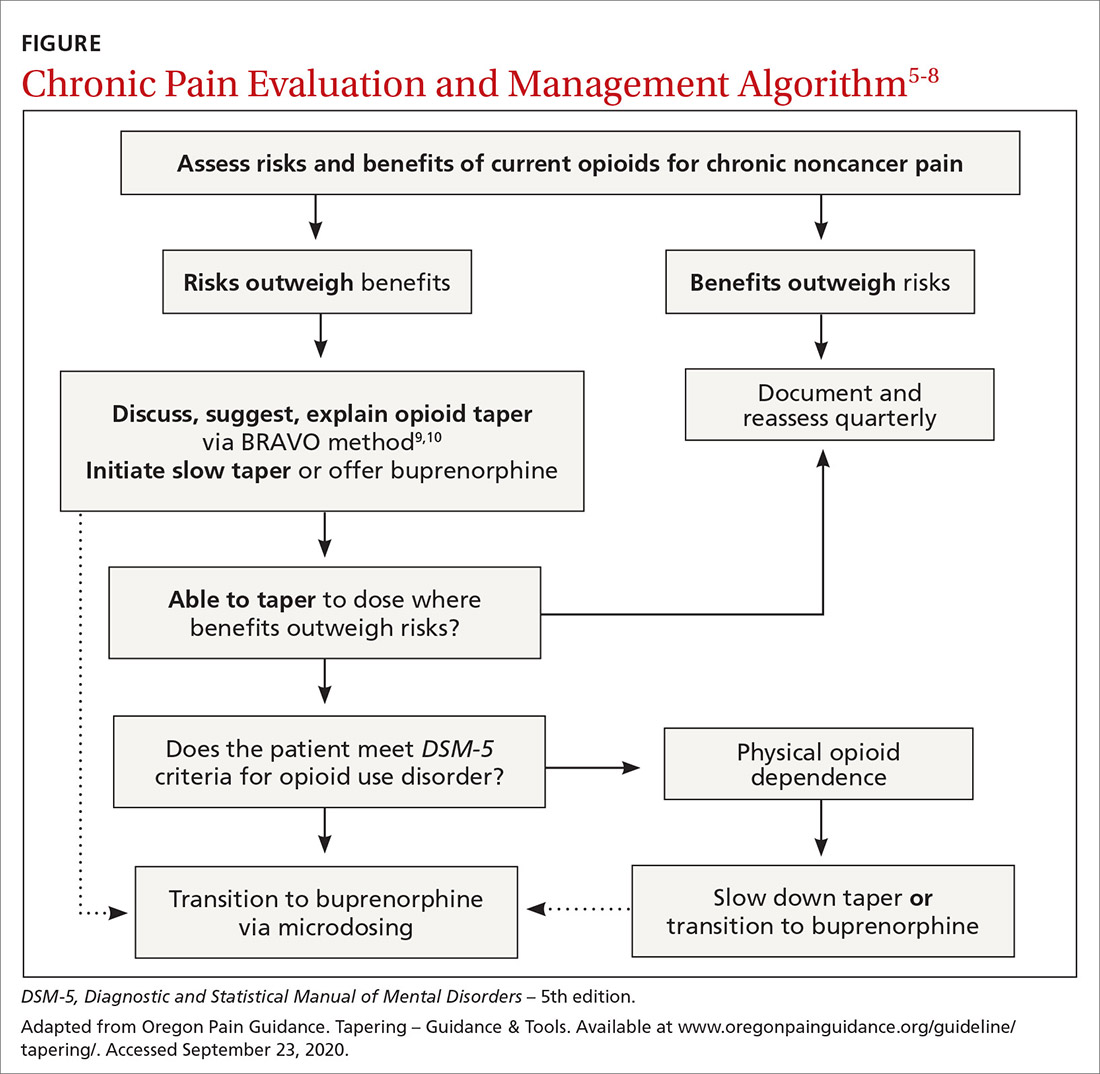

Practical approaches exist. Excellent examples of modern pain care have been developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, and state-level initiatives such as the Oregon Pain Guidance.6-8 All use a similar clinical algorithm (FIGURE). If pain is poorly controlled, a slow medically supervised tapering of opioids is indicated.

It can be challenging to raise the subject of opioid tapering with patients; I use Stanford’s BRAVO method to guide these conversations.9,10 At my facility, we are tapering about 50 legacy opioid patients, and most are surprised to find that their pain is the same or better with reduced to no opioids, with fewer adverse effects. Many are happier on sublingual buprenorphine, a safer opioid analgesic.11 The algorithm shown in the FIGURE and the BRAVO method should be more widely used within our specialty for a safe and patient-centered approach to chronic pain.

Above all, let the patient know that you are with them on this journey to safe pain management. Start the conversation: “I’ve been thinking a lot about your chronic pain and how best to help you with it. Our understanding of what opioids do for pain has changed, and I worry they’re causing more harm than good now. This is a scary thing to talk about, but I’ll be with you every step of the way.”

Matt Perez, MD

Neighborcare Health

Seattle