Pruritus, defined as a sensation that induces a desire to scratch1 and classified as acute or chronic (lasting > 6 weeks),2 is one of the most common complaints among primary care patients: Approximately 1% of ambulatory visits in the United States are linked to pruritus.3

Chronic pruritus impairs quality of life; its impact has been compared to that of chronic pain.4 Treatment should therefore be instituted promptly. Although this condition might appear benign, chronic pruritus can be a symptom of a serious condition, as we describe here. When persistent pruritus is refractory to treatment, systemic causes should be fully explored.

In this article, we discuss the pathogenesis and management of pruritus without skin eruption in the adult nonpregnant patient. We also present practice recommendations to help you determine whether your patient’s pruritus is indicative of a serious systemic condition.

An incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of pruritus

The pathophysiology of pruritus is not fully understood. It is generally recognized, however, that pruritus starts in the peripheral nerves located in the dermal–epidermal junction of the skin.5 The sensation is then transmitted along unmyelinated slow-conducting C fibers to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.5,6 There are 2 types of C fibers that transmit the itch impulse6: A histamine-dependent type and a non-histamine-dependent type, which might explain why pruritus can be refractory to antihistamine treatment.6

Once the itch impulse has moved from the spinal cord, it travels along the spinothalamic tract up to the contralateral thalamus.1 From there, the impulse ascends to the cerebral cortex.1 In the cortex, the impulse triggers multiple areas of the brain, such as those responsible for sensation, motor function, reward, memory, and emotion.7

Several chemical mediators have been found to be peripheral and central inducers of pruritus: histamine, endogenous opioids, substance P, and serotonin.2 There are indications that certain receptors, such as mu-opioid receptors and kappa-opioid receptors, are key contributors to itch as well.2

A diverse etiology

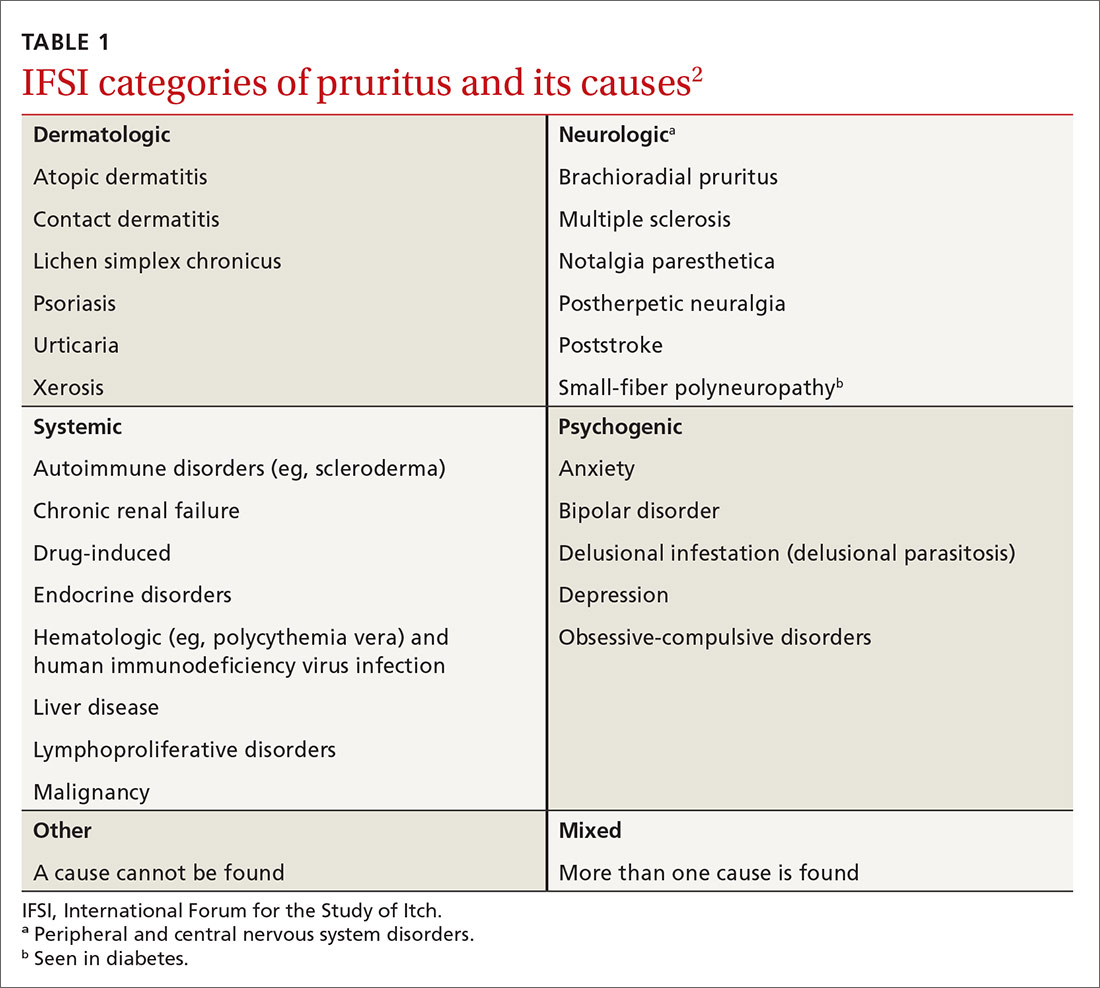

The International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) has established 6 main categories of causes of pruritus(TABLE 1)2:

- dermatologic

- systemic

- neurologic

- psychogenic

- mixed

- other.

Continue to: In this review...