according to new research.

This the latest sign of a long-term decline, and it “poses a broader concern for a specialty that defines itself by its comprehensive scope of practice,” said the study investigators of the Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., in a written statement. “This is consistent with previous Robert Graham Center research that reported a similar steady decline from 1992 to 2002.”

Self-reported data from family physicians indicate that 84.3% cared for children aged 18 years and under in 2017, compared with 83.0% in 2018, based on a cross-sectional analysis of data gathered from 11,674 family physicians who completed the practice demographic questionnaire attached to the American Board of Family Medicine’s certification exam in 2017 and 2018.

“This current trend is unsettling, because family physicians provide the majority of pediatric care in rural and pediatrically underserved areas of the United States,” study author Anuradha Jetty, MPH, and coauthors said in the statement.

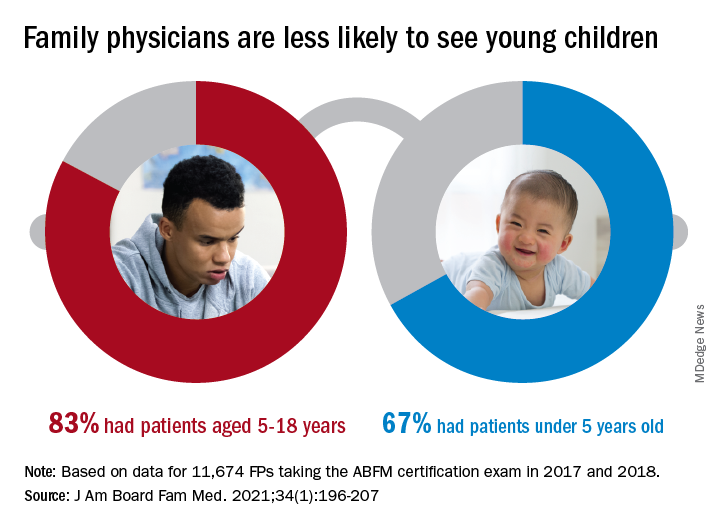

The analysis also offers a snapshot of the current state of pediatric care offered by family physicians. In 2017 and 2018, FPs were more likely to see patients aged 5-18 years than those under age 5 (83.0% vs. 67.0%), with variation by age, location, and race/ethnicity, said Ms. Jetty and colleagues, in their new paper.

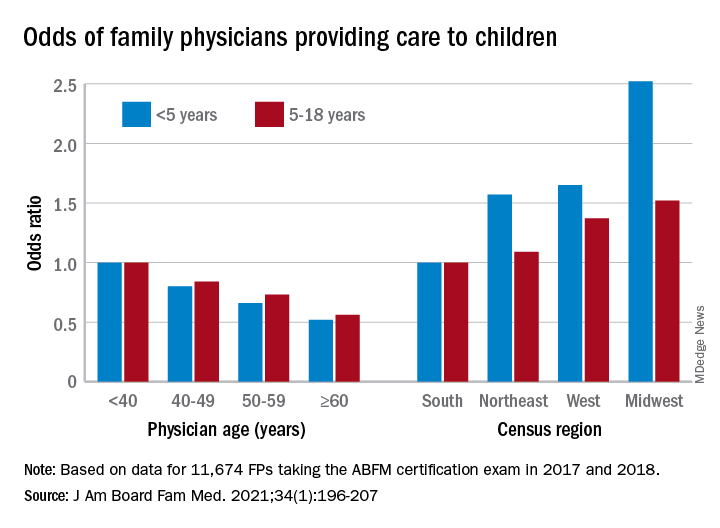

FPs aged 60 years and older were much less likely to see pediatric patients, compared with those under age 40: odds ratios were 0.52 for children under 5 and 0.56 for children 5-18. Regional variation was even more pronounced: Compared with their colleagues in the Southern states, Midwestern FPs were 1.52 times as likely to treat children aged 5-18 and 2.52 times as likely to treat children under age 5, the investigators reported.

Non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic family physicians had significantly lower odds of seeing pediatric patients, relative to non-Hispanic White family physicians, as did FPs who were international medical graduates (OR, 0.74), compared with those who trained in the United States, they said.

“Female gender was associated with seeing pediatric patients in a prior study using 2006-2009 [American Board of Family Medicine] data; however, we found no such association in 2017-2018,” Ms. Jetty and associates noted.

“Many diverse drivers likely influence the findings we observed, including organizational, personal, social, and economic factors,” they wrote, suggesting that the policies of some HMOs “may limit scope of practice for employed physicians,” while those who practice in areas of low pediatrician density might “capitalize on a market opportunity ... more than physicians in pediatrician-saturated areas with greater competition for young patients.”

The overall shortage of primary pediatric care may be a matter of debate, the investigators said, but “there is undoubtedly significant variability in the regional supply of pediatric primary care physicians and thus areas where family physicians are needed to meet current pediatric workforce demand.”

The authors reported no conflicts.