What do we mean when we talk about pain? Traditionally pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.1 Pain can result when intense or noxious stimuli activate peripheral nociceptors. It serves as a warning against impending tissue damage and acts reflectively to protect against or minimize that damage.

We have known since the time of Descartes about the existence of an ascending sensory pain pathway that sends “distress” signals from the source of tissue damage to the brain. We also know of the Gate Control theory described by Melzack and Wall in 1965, in which stimulation of the skin evokes responses that transmit signal injury to transmission cells (the “gate”) in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord that continues to the brain, triggering response signals that modulate the activity of inhibitory cells (which close the “gate”), thereby decreasing the intensity of pain.2 But how do we explain pain in the absence of tissue damage, pain that is not triggered in the periphery, that often appears long after the noxious stimulus has stopped exerting its unpleasant effect?

Types of chronic pain

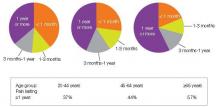

An estimated 116 million American adults suffer from chronic pain, defined as pain that lasts more than 3 months after onset and well into the phase of healing.1,3 According to a 2006 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with a special focus on pain, almost 57% of adults age 65 or older and 37% of younger adults ages 20–44 reported pain that lasted one year or more [Figure 1].4 Chronic pain exacts a cost of between $560 billion and $635 billion annually in medical treatment and lost productivity.5 There is a tremendous need to understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms of chronic pain in an effort to develop new, more effective treatments for these patients. This understanding may come as a result of our recent advances in visualizing the peripheral and central processes involved in pain. The emerging data suggest that for some individuals central factors play a key role in the maintenance and establishment of certain chronic pain conditions. That is, for some, the problem is really not inthe periphery.

| FIGURE 1: Pain duration by age group, 1999-2002 |

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2006. Data from theNational Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. |

Knee and hip pain. When peripheral tissue damage is unavoidable, the inflamed tissues and those nearby become hypersensitive, a protective response to guard the area during the period of healing. Conditions like chronic low-back pain and knee or hip osteoarthritis classically have been thought to be due to inflammation or damage to tissues in the back, knee, or hip. However, recent studies show that these conditions may have complex factors entailing both the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) of patients with radiographic evidence of structural damage to the knee due to osteoarthritis found discordance between the amount of damage visible on x-ray and patients’ self-report of the degree of pain. In 319 patients with radiographic stage 2–4 knee osteoarthritis, only 47% reported knee pain, suggesting that something more than the degree of tissue injury was involved in the perception of pain.6,7 One explanation of these findings is that pain is a complex system incorporating structural changes, peripheral and central pain mechanisms, and subjective factors, including the patient’s history, psychological experience, genetics, and culture.

Diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia. Chronic neuropathic pain results when there is actual damage to the nervous system—the peripheral nerve, dorsal root, or central nervous system. Peripheral neuropathic pain occurs after damage or alterations to sensory neurons. Some neuropathic pain disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia, are well-defined disorders in which symptoms are unrelated to a stimulus and pain is related to peripheral as well as central processing.8

Stroke. Central poststroke pain, in which pain and hypersensitivity occurs in a body part due to injury to the corresponding part of the brain affected by the cerebrovascular lesion, is also considered a neuropathic pain syndrome. The onset of central poststroke pain typically occurs more than one month after the stroke, and exists with somatosensory abnormalities.9-11 For these types of neuropathies, altered function due to loss or damage of neuronal tissue is likely the cause of the pain condition.

Many of the people suffering from these central chronic pain conditions find it difficult to obtain relief, and probably will not benefit from surgeries or manipulations in the periphery. Instead, they may benefit from a targeted approach that addresses the central nervous system.