A recent outbreak of Hepatitis A—linked to imported green onions served at a restaurant in Pennsylvania—sickened close to 600 patrons and restaurant staff and killed 3.1 Large-scale hepatitis outbreaks are uncommon. But this well-publicized event drew attention to Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infections and the issue of food safety, and it provides an example of the importance of accurate diagnosis, prompt reporting to public health authorities, and implementation of the preventive measures discussed here to lessen the community impact of this infectious disease.

Those at risk of infection

Hepatitis A virus is passed fecal-orally, and infection usually results from person-to-person transmission within a household or between sexual partners. Young children with hepatitis A are often the source of infection for adults. Day care centers are an important source of infection of children, staff, and parents of children.

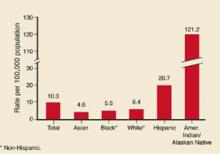

Disease incidence varies considerably by race/ethnicity and geography. American-Indians have the highest rates; Hispanics have the second-highest (Figure 1). Rates are higher in the western US (Figure 2).

Persons at highest risk for HAV infection include travelers to developing countries, men who have sex with men, users of illicit drugs, those with clotting factor disorders, and persons who work with nonhuman primates. Those who have chronic liver disease are at higher risk of fatal, fulminate infection.

Surprisingly, workers in day care centers, health care institutions, schools, and sewage facilities appear not to be at higher than average risk for the community.

FIGURE 1

Hepatitis A by race/ethnicity

Rates of reported hepatitis A by race/ethnicity—United States, 1994. Source: CDC, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

FIGURE 2

Average reported cases of hepatitis A per 100,000 population, 1987–1997

Approximately the national average of reported cases during 1987–1997, by county. Source: CDC.

Clinical onset is sudden

Symptoms of illness appear suddenly and include fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, dark urine, and jaundice. By the time symptoms appear, the infection has been incubating from 2 weeks to 2 months (average, 28 days).

Mild symptoms without jaundice are much more likely in children (70%) than in adults (30%). Symptoms usually last less than 2 months but can occasionally persist or relapse for up to 6 months.

Confirm with IgM testing. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing for anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which is present before symptoms appear and persists for 6 months. Anti-HAV IgG also occurs early in infection but persists lifelong and cannot be used to distinguish old from current infection. Infectivity is highest in the 2 weeks before jaundice appears.

Matching prevention measures to patient needs

Two forms of HAV prevention are available: immune globulin (IG) and Hepatitis A vaccine.2

Immune globulin

For those traveling to high-risk areas, pre-exposure prophylaxis IG at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg intramuscularly offers up to 3 months of protection; a dose of 0.06 mL/kg intramuscularly provides protection up to 5 months.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended at a dose of 0.02 mL/kg and, if given within 2 weeks of exposure, is 85% effective in preventing disease. If it can be provided within 2 weeks of the last exposure, IG is recommended for all unvaccinated household and sexual contacts of those with laboratory confirmed hepatitis A, and for those who have shared illicit drugs with an infected person.

Caveats. Immune globulin can interfere with the effectiveness of both mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and varicella vaccine. MMR administration should be delayed for 3 months and varicella vaccine for 5 months following IG administration. Immune globulin should not be given for at least 2 weeks after MMR vaccination or three weeks after varicella vaccination. Some IG preparations contain thimerosal; these should not be used in infants or pregnant women.

Hepatitis A vaccine

Two single-antigen hepatitis A vaccines are marketed, both of which are prepared from inactivated virus. Neither product is approved for use in children younger than 2 years. Both vaccines must be given in 2 doses, 6 months apart, for full protection; although in over 90 % of adults, protective antibody levels develop within 4 weeks of the first dose. The Table lists the dose and schedule for each hepatitis A single-antigen vaccine.

Candidates for hepatitis A vaccine:

- Children who live in states, counties, or communities with average annual hepatitis A rates of 20/100,000 or greater

- Travelers or those working in countries with high or intermediate rates of HAV infection (Figure 3)

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of illicit drugs

- Those who work with HAV in laboratories or with non-human primates

- Those with clotting factor disorders

- Those with chronic liver disease

Vaccines are safe. Hepatitis A vaccine does not interfere with other vaccines, appears safe in pregnancy, and causes only minor reactions such as pain and redness at the injection site, headache, or malaise. No credible evidence of serious complications from the vaccine exists. Since it takes 4 weeks for a full immune response to the vaccine to develop, those who need protection sooner should receive IG or both IG and vaccine administered at different sites.