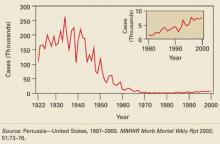

The incidence of pertussis in the United States declined dramatically after the introduction of pertussis vaccine in the 1940s. Before that, an average of 160,000 cases of pertussis (150/100,000 population) occurred each year, resulting in 5000 deaths. FIGURE 1 shows how pertussis incidence declined steadily through 3 decades to reach a low of 1010 cases in 1976.

While other vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio, measles, rubella, diphtheria, and tetanus have been eradicated or have declined to only a few cases each year, pertussis has made a slight comeback. The number of cases began increasing in the 1980s and reached a level of 7000 to 8000 cases annually between 1996 and 2000 (see insert in FIGURE 1). There were 11,647 cases in 2003.

While these numbers are small compared with all cases that occurred in the prevaccine era, the increase is cause for public health concern.

FIGURE 1

Number of reported pertussis cases, by year—1922–2000

Unique features of this rebound

The recent rise of pertussis displays several notable trends:

- Disease incidence now ebbs and flows in 3- to 4-year cycles

- The proportion of cases occurring among adolescents and young adults has increased. TABLE 1 shows the age breakdown of reported pertussis cases for 2001. Infants still account for the highest proportion of cases (29%) and the highest attack rates (55 cases per 100,000); but half of reported cases now appear in those age 10 years and older

- Nonimmunized or incompletely immunized infants are usually exposed to the disease by older household members, and not by same-age cohorts

- Since the disease presents as nonspecific cough in adolescents, it is often not diagnosed. The incidence is probably much higher than the reported number of cases would indicate.

TABLE 1

Pertussis-related hospitalizations, complications, and deaths, by age group—United States, 1997–2000

| AGE GROUP | NO. WITH PERTUSSIS | HOSITALIZED NO. (%) | COMPLICATIONS | DEATHS NO. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEUMONIA* NO. (%) | SEIZURES NO. (%) | ENCEPHALOPTHY NO. (%) | ||||

| < 6 mo | 7203 | 4543 (63.1) | 847 (11.8) | 103 (1.4) | 15 (0.2) | 56 (0.8) |

| 6–11 mo | 1073 | 301 (28.1) | 92 (8.6) | 7 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| 1–4 years | 3137 | 324 (10.3) | 168 (5.4) | 36 (1.2) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (<0.1) |

| 5–9 years | 2756 | 86 (3.1) | 68 (2.5) | 13 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.1) |

| 10–19 years | 8273 | 174 (2.1) | 155 (1.9) | 25 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | 0 |

| ≥ 20 years | 5745 | 202 (3.5) | 147 (2.6) | 32 (0.6) | 3 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) |

| Total | 28,187† | 5630 (20.0) | 1477 (5.2) | 216‡ (0.8) | 26 (0.1) | 62 (0.2) |

| *Radiographicaly confirmed. | ||||||

| †Excludes 92 (0.3%) persons of unknown age with pertussis. | ||||||

| ‡Excludes one person of unknown age with seizures. | ||||||

| Source: Pertussis—United States, 1997–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rpt 2002; 51:73–76. | ||||||

Why the increase in cases?

Several possible causes could account for the increased incidence in reported pertussis. For one, the efficacy of the vaccine wanes with time after vaccination. Adolescents and young adults are left susceptible because, until recently, no vaccine has been available for persons after their 7th birthday. This, however, has been true for decades and does not explain recent increases.

The Bordetella pertussis bacteria may have genetically drifted to become less susceptible to vaccine-induced antibodies, or the apparent increase in cases could actually be just an increase in case detection.

It is also possible that the recent emphasis on avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use for respiratory infections has had the unanticipated consequence of decreasing previously fortuitous treatment of undiagnosed pertussis among older age groups.

New tool in fight against pertussis now available

Two products with tetanus toxoid—reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines adsorbed (Tdap)—have been licensed for active booster immunization against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis as a single dose. BOOSTRIX (GlaxoSmithKline) is for persons aged 10 to 18 years, and ADACEL (Sanofi Pasteur) is for those aged 11 to 64 years.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended Tdap for universal use among adolescents aged 11 to 12 years, and may in the future recommend its use periodically for all adults.

Rethink your approach to older patients

Clinical presentation of pertussis in an adolescent and adult is nonspecific. After an incubation period of 1 to 3 weeks, pertussis infection appears as a mild respiratory infection or the common cold.

After 1 to 2 weeks, the nonproductive cough can evolve into paroxysms of severe coughing (causing apnea), a posttussive inspiratory whoop, and vomiting. The inspiratory whoop and apnea are usually absent in previously immunized adults and adolescents. The cough gradually diminishes but can persist for up to 3 months.

Suspect pertussis in any adolescent or adult who has had a cough for 2 weeks or longer, even if the paroxysms and post tussive symptoms are absent.

Infants exhibit more severe symptoms and suffer higher rates of complications, including severe apnea, hospitalization, seizures, secondary pneumonia, and death (TABLE 1).

Required laboratory confirmation

For any patient with suspected pertussis, obtain an aspirate of the posterior nasopharyngeal region or swab it for culture. The specimen can be collected by inserting a Dacron nasopharyngeal swab into the nostril to reach the posterior nares and leaving it in place for 10 seconds (FIGURE 2). If the specimen cannot be streaked onto a special enriched culture medium, place it in a special transport medium and refrigerate it until sent to the laboratory. Local or state health departments can often assist with obtaining the transport medium.