- Consider any alteration of mental status that follows a trauma to be a concussion, whether or not there is also a loss of consciousness (A).

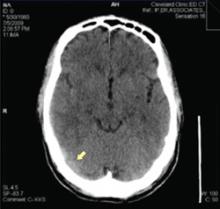

- Don’t order neuroimaging routinely; it is not necessary for diagnosing concussion. Neuroimaging is important, however, for patients who exhibit prolonged unconsciousness, focal neurologic deficits, or worsening symptoms (A).

- Treat post-concussive headache, a common complaint, with acetaminophen or ibuprofen (A).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

It’s 7 AM and you’re just finishing breakfast when you get a call from an emergency room (ER) resident telling you that Max, a 14-year-old patient of yours, has just been brought in by ambulance after a car accident. When the EMTs arrived at the scene, the car was totaled. The driver, Max’s older brother, had no injuries other than a minor abrasion on his nose, but Max was unconscious.

By the time you get to the hospital, Max is sitting up and talking. He says his head aches and he’s feeling dizzy. He’s having difficulty comprehending what he’s doing in the ER, doesn’t know how he got there, and has no memory of the accident. He has a small contusion on his forehead, but no other apparent injuries.

You question Max’s brother, and he tells you he hydroplaned while driving in the rain, and skidded into a telephone pole. He was OK, but Max was slumped down in his seat and unresponsive. The driver of another car had seen the accident and called 911.

How would you evaluate Max’s condition? What tests would you perform? And what would you tell his worried parents?

A diagnosis with variable—and often subtle—symptoms

Max’s situation fits the American Academy of Neurology’s (AAN) definition of concussion, ie, an alteration in mental status following a trauma that may or may not result in a loss of consciousness.1 According to the AAN, this change in mental status usually lasts less than 24 hours and may be coupled with symptoms of vertigo, headache, nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, photophobia, blurred vision, and anterograde or retrograde amnesia.2-5

The presenting signs and symptoms of concussion are so variable that the condition can be difficult to diagnose. Many patients display nothing more than a so-called vacant stare. Others experience only minor symptoms, such as headache or nausea. Max’s loss of consciousness is relatively rare, occurring in only about 10% of concussion cases.6

At least 1.4 million concussions occur in the United States each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).7,8 The incidence, though, is probably greater than the CDC reports, because so many cases are unrecognized or unreported. Falls, motor vehicle accidents, and sports injuries are the leading causes, with some 250,000 football-related concussions reported each year.4,7,9,10

Common, yes, but challenging, too

As common as concussion is, it can—at times—be challenging to recognize. These tips can help:

Do a mental status exam. Ask the patient what his name is, what today’s date is, and where he is now. See if he can repeat 3 words immediately after you say them and then 5 minutes later. Can he spell the word “world” backwards?

Get the story. If the patient can’t remember the incident or isn’t able to tell you about it, try to get the details from a witness. If the patient is able to talk, ask if she or he remembers what was happening just before the accident and afterwards. Does the patient seem to have difficulty concentrating on your questions? Seem alert, or confused? Can the patient (or a witness) tell you how the injury occurred, how severe the impact was, and whether there was loss of consciousness—all important factors in the diagnosis.1 Has the patient ever had a concussion before? Were there any sequelae?

Perform a neurologic evaluation. Assess cranial nerves and cerebral, cerebellar, and peripheral nerve function. Check pupils for reactivity and symmetry. See whether the patient has full and appropriate eye movement in all directions. Assess grip strength and muscle strength in arm and leg flexion and extension. Test for abnormalities in reactions to pinprick, temperature, and vibration in all extremities. Ask the patient to close his eyes, extend the arms with palms up, and hold the position for 20 to 30 seconds. If the patient fails this assessment for pronator drift, consider a diagnosis of muscle weakness or cerebellar disease. Check gait for ataxia and speech for fluency and coherence.

When a CT is required