TABLE

Causes of acute and chronic orchialgia1,3,4

Acute

|

Chronic

|

Chronic testicular pain can also be psychogenic, often relating to a history of sexual abuse or relationship stress. One study examining comorbid psychological conditions in men with chronic orchialgia identified a somatization disorder in 56% of the patients, nongenital chronic pain syndromes in 50%, and major depression or chemical dependency in 27%.2 Overall, however, estimates suggest that in about 25% of patients with chronic orchialgia, no identifiable etiology is found. 1

Establish a baseline with a physical exam

Conduct a physical examination of the scrotum, testes, spermatic cords, penis, inguinal region, and prostate as a baseline measurement in a patient who presents with chronic orchialgia.3,4 An initial urinalysis should be performed to rule out infection or identify microscopic hematuria, which may prompt a more targeted work-up and therapeutic plan. Take a thorough medical and psychosocial/ sexual history, as well.

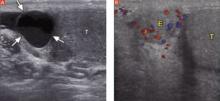

Order an ultrasound of the scrotum and testes, the accepted gold standard to highlight structural abnormalities of the testicles. The addition of color Doppler makes it possible to find areas of hypervascularity, an indication of inflammation in the testicle and epididymis (FIGURES 2A AND B).

FIGURE 2

Well-circumscribed extratesticular mass

In the image at left, ultrasound reveals an anechoic mass (arrows), representing either an epididymal cyst or spermatocele, superior to the testicle (T). A color Doppler image (right) reveals increased vascularity to the epididymis (E), as compared with the testicle.

Epididymal cysts are common findings on scrotal ultrasound; they are frequently incidental, but may relate to the patient’s pain, depending on the size of the cyst. Smaller cysts that do not correlate with pain do not require treatment. Larger, painful cysts can be treated with aspiration or injection with a sclerosing agent—or with surgical excision, which offers the highest potential cure rate.3,4 A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast is the best way to find genitourinary system calculi, which could be the source of referred renal pain to the groin and scrotum. A contrast-enhanced CT is best to evaluate for solid renal masses.

Start with the most conservative treatment

In the absence of any findings that require surgical intervention, start conservatively.

Initiate a trial of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for at least 1 month. Although this is the standard first-line treatment, NSAIDs have been shown to help only a small percentage of patients with chronic orchialgia, and only on a short-term basis.1,3,4

Recommend scrotal elevation with supportive undergarments to decrease venous congestion. Tell the patient, too, that modifying his seated posture to avoid scrotal pressure may alleviate pain and poses no discernible risk of worsening orchialgia.5

Treat suspected STIs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that in men 14 to 35 years of age, epididymitis is most commonly caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea.6 In males younger than 14 or older than 35, epididymitis is most commonly caused by urinary coliform pathogens, including Eschericia coli.

If epididymitis is suspected to be due to chlamydia or gonorrhea, treatment should include either doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 10 days or a single dose of azithromycin 1 g orally (for chlamydia eradication) and a single dose of ceftriaxone 125 mg intramuscularly (for gonorrhea eradication).6,7 If coliform bacteria is suspected, order a standard dose of a quinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin 500 mg/d) for 10 days.6 For refractory cases, treatment with a standard dose of a quinolone for 4 weeks is recommended.6

It is generally reasonable to treat most patients empirically for suspected epididymitis with antibiotics if no other identifiable etiology can be determined. Multiple antibiotic treatments should be avoided, however, in the absence of either an identifiable urogenital infection or ultrasound findings consistent with epididymitis (eg, congestion and enlargement). Antibiotics have not been shown to decrease the severity of chronic orchialgia and their use, unless clearly indicated, may lead to drug resistance.3