Public health efforts have decreased the incidence of gonorrhea over the past several decades, but this progress is threatened by emergent bacteria resistance to the few remaining antibiotics available to treat it.

Gonococcal resistance to penicillin and tetracycline began in the 1970s and was widespread by the 1980s. Resistance to fluoroquinolones developed during the last decade and led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2007 to stop recommending this class of antibiotics for treatment of gonorrhea.1 (See “The decline of gonorrhea: A success story now threatened by antibiotic resistance”.)

Given the speed with which gonococci developed resistance to fluoroquinolones, the CDC sees as inevitable the eventual development of resistance to cephalosporins—the currently favored agents for gonorrhea.2 This is the main reason behind the new recommendations for treating all cases of gonorrhea with both a cephalosporin and azithromycin, whether or not co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis is documented or suspected.3

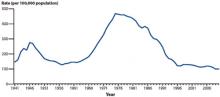

The reported rate of gonorrhea rose steadily from the early 1960s until the mid-1970s, when it was close to 500 cases per 100,000. With implementation of the national gonorrhea control program, the annual rate began to fall, and by the mid-1990s it had declined by 74%. Between 1996 and 2006, the rate remained at about 115 cases per 100,000. Between 2006 and 2009, it decreased to the lowest rate since national reporting began, but increased 2.8% between 2009 and 2010 (FIGURE 1).

The highest rates of gonorrhea are in the South (FIGURE 2) and in women ages 15 to 24 and men ages 20 to 24 (FIGURE 3). Rates are highest among blacks (432.5 cases per 100,000), followed by American Indians/Alaska natives (105.7) and Hispanics (49.9). Between 2009 and 2010, gonorrhea rates increased among American Indians/Alaska natives (21.5%), Asians/Pacific Islanders (13.1%), Hispanics (11.9%), whites (9.0%), and blacks (0.3%).

Recent trends in Gonococcus susceptibility to cephalosporins have the CDC concerned. While cephalosporin resistance remains rare, the proportion of Gonococcus isolates that have shown elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations to cephalosporins has increased.

Gonorrhea control depends in part on appropriate screening of individuals at risk (TABLE). Risk factors for gonorrhea include a history of previous gonorrhea infection, other sexually transmitted infections, new or multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, sex work, and drug use. Risk factors for pregnant women are the same as for nonpregnant women. Prevalence of gonorrhea infection varies widely among communities and patient populations.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/surv2010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

FIGURE 1

A decline in gonorrhea that began in the mid-1970s*

*The initiation of a national gonorrhea control program reaped immediate benefits that have continued through the present.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2010. Gonorrhea—rates, United States, 1941-2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/surv2010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

FIGURE 2

Gonorrhea prevalence, 2010

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2010. Gonorrhea—rates by state, United States and outlying areas, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/10/surv2010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

FIGURE 3

Gonorrhea prevalence by age and sex, 2010

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2010. Gonorrhea—rates by age and sex, United States, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/surv2010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

Augment therapy, follow up thoroughly

Family physicians can assist with public health efforts to control gonorrhea and delay the development of cephalosporin resistance by screening for and detecting the infection, diagnosing those with symptoms, and treating according to newer recommendations. It’s also essential to report cases to local public health departments, assist with finding and treating sexual contacts of infected individuals, and immediately report suspected treatment failures.

A 2-drug regimen is imperative. The latest recommendation for treating gonorrhea is ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose and azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose. Until 2010, the dose of ceftriaxone had been 125 mg. This dual drug regimen is recommended for several reasons: As with using multiple drugs to treat tuberculosis, it is hoped dual drug therapy will slow development of resistance to both cephalosporins and azithromycin; co-infection with C trachomatis remains a significant problem; and the combination may be more effective against pharyngeal gonorrhea, which is hard to detect.

Alternative regimens. Cefixime 400 mg orally as a single dose is an option in lieu of ceftriaxone, but is not preferred because of the higher number of reported failures of treatment with oral cephalosporins and less efficacy against pharyngeal disease.3 Other injectable cephalosporins are also an option, but less is known about their effectiveness in treating pharyngeal infection. Injectable options include ceftizoxime 500 mg IM, cefoxitin 2 g IM with probenecid 1 g orally, and cefotaxime 500 mg IM.