Although effective for grades III and IV hemorrhoids, conventional hemorrhoidectomy is known to entail a significant recovery period and postoperative pain (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).

The newest treatment option for grades III and IV hemorrhoids, the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids, is an effective technique with the potential to incur less pain and a quicker return to work and daily activities (SOR: B).

For patients with severe hemorrhoidal symptoms who do not want, or are unable, to undergo any type of surgical procedure, rubber band ligation is a viable option (SOR: B).

Hemorrhoids represent one of the most common colorectal complaints heard by family physicians. Each year approximately 10.5 million Americans experience hemorrhoidal symptoms; one fourth of those patients consult a physician.1

The most common symptom of internal hemorrhoids is bright red blood that covers the stool or appears on toilet paper or in the toilet bowl. Other symptoms include irritation of the skin around the anus; pain, swelling, or a hard lump around the anus; hemorrhoidal protrusion; and mucous discharge. Excessive rubbing or cleaning around the anus may exacerbate symptoms and even cause a vicious cycle of irritation, bleeding, and itching termed pruritus ani. Hemorrhoids also may thrombose, causing severe pain.

More than half of men and women aged 50 years and older will develop hemorrhoidal symptoms throughout their lifetime.2 Hemorrhoidal symptoms also tend to flare up during pregnancy, when hormonal changes and the pressure of the fetus cause the hemorrhoidal vessels to enlarge.

The likelihood of hemorrhoidal disease increases with age. By age 30, the anal support structure diminishes in function.3 This microscopic evidence, along with increased sphincter tone, may contribute to the progression of hemorrhoids.4

Although hemorrhoidal symptoms may subside after several days, they most often return, causing long-lasting discomfort and pain. Many affected persons—particularly those with severe hemorrhoids—suffer in silence for years before seeking treatment.5 Fortunately, only about 10% of patients have symptoms severe enough to require surgery.6

Differential diagnosis

Many anorectal problems, including fissures, fistulae, abscesses, or irritation and itching, have symptoms similar to those of hemorrhoids and must be ruled out prior to recommending appropriate treatment. In addition, the correlation of rectal bleeding with colorectal cancer becomes stronger with age, as demonstrated in a retrospective study of the diagnostic value of rectal bleeding in relation to a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer.7 Therefore, further evaluation with colonoscopy should be made in patients who are older than 50 years of age, have a family history of colon cancer, and experience fatigue or weight loss or have a palpable mass.8

Classification of hemorrhoids

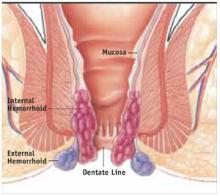

External hemorrhoids originate below the dentate line (FIGURE 1). Internal hemorrhoids are above the line and are classified according to their degree of prolapse:

- Grade I hemorrhoids protrude into the lumen of the anal canal but do not prolapse.

- Grade II hemorrhoids protrude with a bowel movement but spontaneously return when straining stops.

- Grade III hemorrhoids protrude either spontaneously or with a bowel movement, and can be manually reduced.

- Grade IV hemorrhoids have an irreducible prolapse.

This article focuses on a new treatment option for grades III and IV.

FIGURE 1 Mucosal Prolapse and Hemorrhoids

Methods of treating grades III and IV hemorrhoids

Until recently, the recommended treatments for grades III and IV hemorrhoids were limited to rubber band ligation (RBL) and conventional hemorrhoidectomy.

An office procedure not requiring anesthesia, RBL is the use of a latex band to cut off blood flow to the symptomatic hemorrhoid. The procedure is not without complications; there have been several reports of fatal and nonfatal retroperitoneal sepsis after RBL.9,10

Most conventional hemorrhoidectomies are performed in 1 of 2 ways. Outside the United States, the Milligan-Morgan technique, which excises the 3 major hemorrhoidal vessels, is considered the gold standard hemorrhoidectomy. Developed in 1937 in the United Kingdom, the surgery is also known as “open” hemorrhoidectomy because the incisions, which are separated by bridges of skin and mucosa, are left open to avoid stenosis. The Ferguson technique, developed in the United States in 1952, differs from the Milligan-Morgan procedure in that the incisions are sutured shut. Accordingly, it is commonly known as “closed” hemorrhoidectomy.

Regardless of technique, conventional hemorrhoidectomy is known to involve significant postoperative pain and an extended recovery time that precludes a fast return to work and daily activities.

A new stapling technique, the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH), was introduced in the mid-1990s and has been used extensively since then. Also known as stapled hemorrhoidopexy, stapled hemorrhoidectomy, or Longo stapled circumferential mucosectomy, PPH involves the use of a specially designed circular stapler that is inserted through the anus (FIGURE 2). The procedure reduces the prolapse of hemorrhoidal tissue by excising a band of the prolapsed rectal mucosa/internal hemorrhoid. The remaining hemorrhoidal tissue is drawn back into the correct anatomic position within the anal canal.