• Consider starting a course of systemic corticosteroids for a patient with erythroderma, fever, and multiorgan involvement when you strongly suspect a drug reaction is the cause—and have ruled out infection. C

• Suspect Stevens– Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) in a patient with widespread and rapidly progressive desquamation, fever, hypotension, and end-organ involvement. C

• In assessing the severity of skin pain, consider the location; involvement of the eyes, perineum, and hands are associated with greater morbidity. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The usual approach to dermatologic conditions—honed pattern recognition, a deliberate differential diagnosis, and empiric treatment with longer follow-up—runs counter to the response that dermatologic red flags require. Because patients with signs and symptoms associated with dermatologic emergencies have the potential for rapid clinical deterioration, urgent action is paramount.

With this in mind, we’ve focused on 4 red flags—erythroderma, desquamation, skin pain, and petechiae/purpura—as a starting point, rather than presenting a list of dermatologic emergencies and discussing each diagnosis in turn. The text, tables, and images on the pages that follow will increase your awareness of dermatologic presentations that require an immediate response and help you differentiate between signs and symptoms of serious skin disorders and benign findings that might be described as red flag mimics (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1

Conditions that mimic dermatologic emergencies

| Red skin | |

| Diagnosis | Key discriminating features |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | Itchy, rather than painful |

| Red man syndrome | History of vancomycin infusion |

| Stasis dermatitis | Stasis dermatitis location (lower extremities), pruritus |

| Sunburn | History, sun-exposed areas |

| Desquamation | |

| Diagnosis | Key discriminating features |

| Bullous impetigo | Localized; no systemic manifestations |

| Postinfectious desquamation | Subungual location common; occurs during convalescent phase of illness |

| Petechiae and purpura | |

| Diagnosis | Key discriminating features |

| Local trauma | History and location |

| Pigmented purpuric dermatosis | History and healthy appearance |

| Viral exanthema | Healthy appearance |

Erythroderma: Red skin that’s life-threatening

From an etymological perspective, “erythroderma” simply means red skin. Clinically, however, it is defined as extensive erythema, typically covering ≥90% of the skin surface (FIGURE 1). True erythroderma can be life-threatening and must always be considered a dermatologic emergency.1,2

Diligent monitoring of the speed of progression and the presence of fever, systemic symptoms, and multiorgan dysfunction is essential. In a case review of 56 children who presented to an emergency department with fever and erythroderma, 45% progressed to shock.3 Some common causes of erythroderma are psoriasis; contact, atopic, and seborrheic dermatitis; pityriasis rubra pilaris; cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; drug reaction; and toxic shock syndrome (TSS).4

Is it a drug reaction? Erythroderma, fever, and evidence of multiorgan involvement in a patient taking any medication—not just a new one—prompts consideration of a drug reaction. Antiepileptics, dapsone, and sulfonamides are the most frequent offenders.5

DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) is characterized by fever, lymphadenopathy, elevated liver enzymes, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia, as well as erythroderma. The rash may be urticarial or morbilliform in appearance; petechiae, purpura, and blisters may be present, as well.

Because fever, leukocytosis, and transaminitis are also suggestive of an infectious etiology, DRESS syndrome is frequently overlooked. As a result, its true incidence is unknown. Estimates range from about one in 1000 to one in 10,000 drug exposures.6

In addition to discontinuing the medication, treatment for DRESS calls for systemic corticosteroids—which may actually be harmful when infection, rather than a drug reaction, is the cause. Thus, it is necessary to maintain a high index of suspicion and to thoroughly review the medication history of

any patient who presents with erythroderma and systemic symptoms.

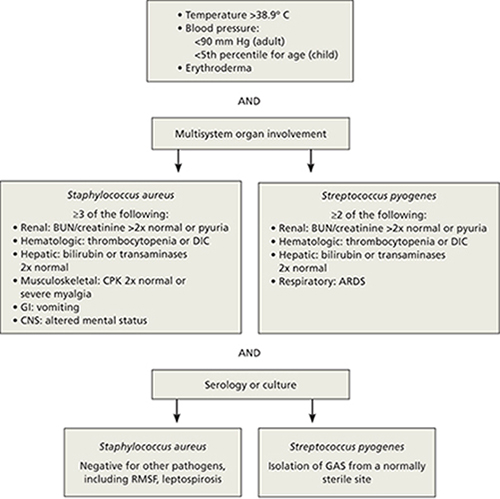

When to suspect toxic shock syndrome. Consider TSS in any patient with erythroderma and hypotension, as well as laboratory evidence of end-organ involvement (including transaminitis, elevated creatinine, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated creatinine kinase). Diagnostic criteria are detailed in FIGURE 2.7 Group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus are the classic infectious causes, but other bacteria have been implicated, as well. In most cases, the responsible bacterium is not known initially.

Because the toxins produced by these streptococcal and staphylococcal strains act as superantigens that fuel the immune response and worsen the shock, patients with a presumptive diagnosis of TSS should begin empiric treatment with an antimicrobial agent that inhibits toxin synthesis, such as clindamycin, immediately.8,9

FIGURE 1

Erythema covering the chest and arms

This patient was given a diagnosis of erythrodermic psoriasis.

FIGURE 2

Diagnostic criteria for toxic shock syndrome

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CNS, central nervous system; CPK, creatinine phosphokinase; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; GAS, group A Streptococcus; GI, gastrointestinal; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Adapted from: Pickering LK, et al, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 2009.7