According to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services, child protection services received more than 3.3 million reports of alleged maltreatment in 2009 that involved about six million children, and about 62% of reports required subsequent action.1 Child abuse is an ever-growing problem that affects children of both genders and in all ages, races, and socioeconomic levels. Few issues generate the concern, anger, and frustration as the abuse or neglect of children.

Primary care providers and emergency department personnel are often the child’s initial point of entry into the health care system. Clinicians who see and treat young patients can play an essential role in the recognition and reporting of child abuse. By frequently reviewing the risk factors for child abuse, its signs and symptoms, and its typical and atypical presentations, clinicians can be prepared to act when appropriate and help break the cycle of child abuse.

LEGAL MANDATES, DEFINITIONS

A relatively new concept, child abuse has been designated as a major public health issue by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization.2-5 In 1874, when it was decided by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to include children within the defined animal kingdom, the movement to protect children began in the United States.6

Both federal and state agencies have created definitions for child abuse and neglect. The key federal legislation to address child abuse and neglect, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), as Amended by the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003,7,8 defines child abuse and neglect as “any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”7 Although ongoing revisions of the CAPTA legislation (the most recent “reauthorization” published in 20109) become increasingly inclusive of both children’s and families’ concerns, this definition has remained consistent.

This is not the case with state definitions, however. Because these vary, it can be difficult to compare rates of reported maltreatment from state to state. Also varying among states, and among counties within some states, are recommendations for substantiation of child maltreatment. The validity of the reported data can be impaired by a lack of coordination or cooperation among different agencies and jurisdictions.

IDENTIFYING THE VICTIMS

The spectrum of child abuse includes multiple forms, which often overlap (see Table 11,9,10), and can almost always have the potential for death.11 According to findings from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, despite worsening economic conditions in 2009, the child maltreatment data compiled that year showed an overall 2% decline in cases of substantiated maltreatment from the previous year.1,11

However, during that same period, child maltreatment–associated fatalities rose 3%, from 1,628 deaths in 2008 to 1,671 in 2009,1 suggesting an increase in the severity of abuse. The emotional, social, and financial ramifications of child abuse affect the local and national community, as well as each child and each family.

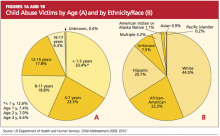

Children younger than 1 year, the most vulnerable to maltreatment, represent the largest proportion of substantiated abuse. One-third of all children reported as abused in 2009 were younger than 4, and children between ages 4 and 7 represented one-fifth of cases.1 Figure 1a1 categorizes the incidence of child abuse by age level, and Figure 1b1 by ethnicity/race.

Risk Factors

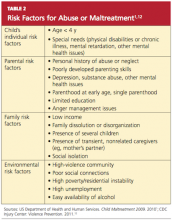

A number of factors, though not necessarily direct causes, have been shown to increase children’s risk for abuse or neglect. These include personal characteristics of the child and parent, and family- or environment-related factors1,12 (see Table 2,1). It is often combinations of risk factors (eg, characteristics of a parent or caregiver in addition to a specific social environment) that are most likely to increase the likelihood of abuse.

Children with special needs (physical disabilities or chronic illness, neurologic impairment, mental health issues) that increase the caregiver’s burden are at increased risk for abuse.1,12 Children with behavior disorders and mental retardation have been found at increased risk for various forms of abuse—neglect and physical or sexual maltreatment13—whereas children with speech or language disabilities are at increased risk for neglect (whether physical, emotional, or even educational14).

Children with physical limitations who experience physical abuse are reportedly subject to more serious injury than their healthier counterparts.14 Their inability to see, hear, move, or communicate, or to dress or bathe themselves independently may make them susceptible to rough, careless, or intrusive personal care, or neglect of their personal needs. Low self-esteem, whatever its cause, also appears to be a significant risk factor for intentional abuse.15