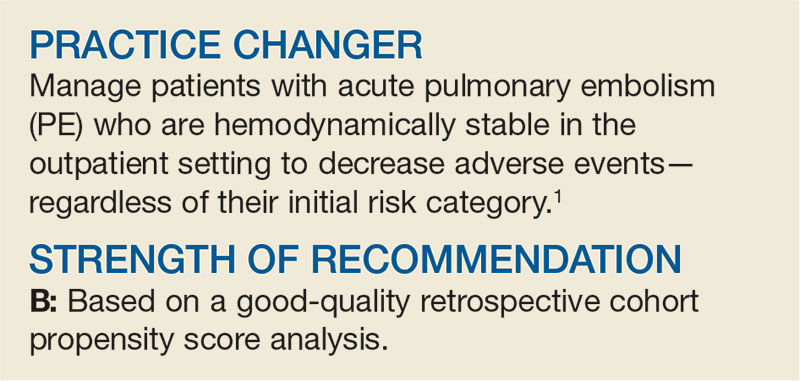

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hypertension presents to the emergency department (ED) with acute-onset shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain after traveling across the country for a work conference. She has no history of cancer, liver disease, or renal disease. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg, and her heart rate, 90 beats/min. You diagnose an acute PE in this patient and start anticoagulation. Should you admit her to the hospital to decrease morbidity and mortality?

According to the CDC, venous thromboembolism (VTE) affects about 900,000 people each year, and about 60,000 to 100,000 of these patients die annually.2 Pulmonary embolism is the third leading cause of death from cardiovascular disease, following heart attack and stroke.3 Prompt diagnosis and treatment with systemic anticoagulation improves patient outcomes and decreases the risk for long-term complications.

The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends home treatment or early discharge over standard discharge (after the first 5 days of treatment) for patients who meet the following clinical criteria: “clinically stable with good cardiopulmonary reserve; no contraindications such as recent bleeding, severe renal or liver disease, or severe thrombocytopenia (ie, < 70,000/mm3); expected to be compliant with treatment; and feels well enough to be treated at home.”3

The guideline states that various clinical decision tools, such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI), can aid in identifying low-risk patients to be considered for treatment at home. The PESI uses age, gender, vital signs, mental status, and a history of cancer, lung, and cardiac disease to stratify patients by risk.4

A systematic review of 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) and 7 observational studies found that in low-risk patients, outpatient treatment was as safe as inpatient treatment.5 This more recent study determines the net clinical benefit of hospitalized versus outpatient management in a wider range of patients with acute PE, regardless of initial risk.1

STUDY SUMMARY

Hospitalization confers no benefit to stable PE patients

This retrospective, propensity-matched cohort study compared rates of adverse events in 1127 patients with acute PE managed in the hospital versus outpatient setting.1 Patients were classified as outpatients if they were discharged from the ED or discharged from the hospital within 48 hours of admission. Patients were included if a symptomatic acute PE was diagnosed via CT or high-probability ventilation-perfusion scan and excluded if they were younger than 19, were diagnosed with a PE during hospitalization, had chronic PE, or were hemodynamically unstable, among other factors. The investigators calculated PESI scores for all patients.

Propensity scores matched patients on 28 characteristics and known risk factors for adverse events to ensure the groups were similar. The primary outcome was rate of adverse events, including recurrent VTE, major bleeding, or death at 14 days. The secondary outcome included rates of the above during the 3-month follow-up period.

Continue to: Of the 1127 eligible patients...