Hypertensive disorders represent one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy.1,2 Based on a nationwide inpatient sample examining more than 36 million deliveries in the United States, the prevalence of associated hypertensive disorders increased from 67.2 per 1,000 deliveries in 1998 to 83.4 per 1,000 deliveries in 2006.3Pregnancy-induced hypertension (also referred to as gestational hypertension or hypertensive disorder of pregnancy)4-6 is estimated to affect 6% to 8% of US pregnancies.1,2

Women who develop severe hypertension during pregnancy may experience adverse effects similar to those associated with mild preeclampsia.2,7,8 In the mother, these may range from elevated liver enzymes to renal dysfunction; and in the fetus, from preterm delivery to intrauterine restriction of fetal growth.7,8

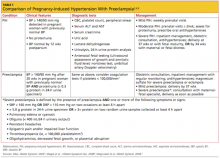

This article will review the risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of pregnancy-induced hypertension. A brief discussion of preeclampsia as it relates to gestational hypertension will be included (see Table 12,6,9).

Classification, Definitions

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is classified as mild or severe. Mild PIH is defined as new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg), occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation. The majority of cases of mild PIH develop beyond 37 weeks’ gestation, and in these cases, pregnancy outcomes are comparable to those of normotensive pregnancies.2,7,8

Severe PIH is defined as sustained elevated blood pressures of ≥ 160 mm Hg systolic and ≥ 110 mm Hg diastolic. In prospective cohort studies in which calcium supplementation and low-dose aspirin use were being investigated for prevention of preeclampsia in healthy pregnant women, those who were severely hypertensive were found to be at increased risk for certain maternal comorbidities (eg, cesarean delivery, renal dysfunction, elevated liver enzymes, placental abruption) and perinatal morbidities (delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and neonatal ICU admission), compared with patients who were normotensive or mildly hypertensive.7,8

The diagnosis of PIH may later be amended or replaced by one of the following diagnoses: preeclampsia, if proteinuria (to be defined and discussed later) develops; chronic hypertension, if blood pressure remains elevated past 12 weeks postpartum; or transient hypertension of pregnancy, if blood pressure normalizes by 12 weeks postpartum.5,6,10

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

Although the pathophysiology of PIH is not well understood, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves abnormalities in the development, implantation, or perfusion of the placenta, and often leads to impaired maternal organ function.6,11 It is not clear whether PIH and preeclampsia are two different diseases that share a manifestation of elevated blood pressure or whether PIH represents an early stage of preeclampsia.4,12 However, women with preexisting hypertension, especially severe hypertension, are at increased risk for preeclampsia, placental abruption, and fetal growth restriction.2

There are some similarities and some distinct differences among the clinical features and risk factors associated with PIH, compared with those of preeclampsia. Risk factors for PIH include a pre-pregnancy BMI of 25 or greater, PIH and/or preeclampsia in previous pregnancies, and history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes. The most important risk factors for preeclampsia include preexisting diabetes or nephropathy, chronic hypertension, PIH or preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, maternal age younger than 18 or older than 34, African-American ethnicity, first pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, history of preeclampsia in the patient’s mother or sister, obesity, autoimmune disease, and an interval between pregnancies longer than 10 years.4-6,13-15

The risk for preeclampsia in patients with PIH is approximately 15% to 25%12,16; according to Magee et al,6 35% of women with PIH onset before 37 weeks’ gestation develop preeclampsia.6,12,17 The risk for recurrence of PIH in subsequent pregnancies is about 26%, whereas women who experience preeclampsia in one pregnancy have a comparable risk for PIH or preeclampsia (about 14% each) in subsequent pregnancies.18

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Blood pressure should be measured and recorded at every prenatal visit, using the correct-sized cuff, with the patient in a seated position.5 Gestational hypertension is a clinical diagnosis confirmed by at least two accurate blood pressure measurements in the same arm in women without proteinuria, with readings of ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥ 90 mm Hg diastolic. It should then be determined whether the patient’s hypertension is mild or severe (ie, blood pressure > 160/110 mm Hg). The patient with severe PIH should be evaluated for signs of preeclampsia, as discussed below.

Patients with mild PIH are often asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is made at a prenatal visit as a result of routine blood pressure monitoring; this is one of many reasons to encourage early and regular prenatal care. Blood pressure may be higher at night in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.10