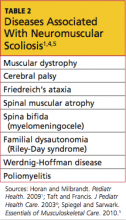

Neuromuscular

Spinal curvature in a patient with a neuromuscular disease is referred to as neuromuscular scoliosis (see Table 2).1,4,5 Most diagnoses within this category are genetic in nature, although some can result from a traumatic brain injury and/or anoxia (eg, cerebral palsy). Given that this disease state is detected early in most patients’ lives, they are generally followed by an orthopedist (or more specifically, by a pediatric orthopedist) once necessary testing, such as radiography or MRI, has been completed.1,15

Syndrome-related

Patients may have certain genetic conditions or syndromes that put them at high risk for scoliosis.

The two conditions most commonly associated with scoliosis are Marfan syndrome (60%) and neurofibromatosis (10% to 15%).1 Many patients in both groups will require MRI for evaluation; given that they are at high risk for lumbar spondylolisthesis (slippage between two lumbar vertebrae), care should be taken to evaluate for this possible secondary finding.16,17 It should be noted that patients with Marfan syndrome are at high risk for cardiac abnormalities, and those with neurofibromatosis, for dural ectasia and/ or Chiari malformations (which would be detected by MRI).16,18

Patients who have undergone chest wall surgery, such as thoracotomy for congenital heart defect repair, should be evaluated for scoliosis. The incidence of scoliosis is elevated in patients with heart defects, and the association is even greater in those who have had chest wall surgery, especially before age 18 months.19

IDIOPATHIC SCOLIOSIS

Because, by definition, no cause is known, idiopathic scoliosis is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Affected patients have a normal neurologic exam and usually have no presenting symptoms or evidence of spinal abnormalities.1 Since 1954, idiopathic scoliosis has been divided into three age-groups, as these periods correspond to phases of increased growth velocity that occur during childhood and adolescence.8,20

Infant

A diagnosis of early-onset scoliosis is made when a child presents with scoliosis before age 5; any affected child between 0 and 3 years of age may be included in the infant scoliosis classification.2 All congenital, neuromuscular, and syndrome-related causes will have been excluded. It is felt among many experts that there is always a genetic or familial component to scoliosis. Therefore, when a child's family history is positive for scoliosis, the child should be aggressively screened, and the family should be educated to observe for signs of scoliosis and seek practitioner involvement as soon as any are evident.2

A thorough examination should be completed to rule out organ involvement in the presence of infant scoliosis.1 It is recommended that any infant with scoliotic curves greater than 20° undergo MRI of the head and spine to rule out central nervous system lesions or structural abnormalities. The risk for respiratory failure-related morbidity and mortality is increased in children with untreated early-onset scoliosis who experience curve progression. Rare progressive curves often can be addressed surgically, preserving spine and trunk growth while also achieving curve correction.2

In the majority of cases of infant scoliosis (75% to 90%), curves are left-sided (levoscoliosis)—in contrast to the right-sided curves (dextroscoliosis) more commonly noted in late-onset (juvenile or adolescent) scoliosis3,21 (see Figure 1). Infant scoliosis is slightly more common in boys (60%) than in girls.21

Neither curve lateralization nor gender makes a difference in treatment.2 Approximately 90% of early-onset curves resolve spontaneously, especially in those who are diagnosed before age 1 year. Progression occurring at a rate of 2° to 3° per year is considered gradual, whereas malignant progression often worsens by 10° or more per year, with the condition possibly becoming severe and disabling.2,21

Any infant given a diagnosis of scoliosis by a practitioner other than a pediatric orthopedist should be referred as soon as possible. On referral, copies of previously obtained radiographs and/or MRI should be presented or sent to the orthopedic practitioner, along with the history and physical exam findings, to avoid the need for repeated imaging.

Juvenile

Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis is diagnosed in patients between ages 4 and 9. Presentation in younger members of this age-group tends to resemble that in infantile idiopathic scoliosis, and children in the middle to upper age range tend to present as adolescent patients do.3 Most juvenile patients' curves will resolve without treatment (especially younger children's).

It is recommended that children with juvenile idiopathic scoliosis undergo MRI to rule out brain or spinal abnormalities. In up to 20% of children younger than 10 with curves exceeding 20°, findings on MRI are abnormal.3 Observation with close monitoring of curve progression is key in this population, especially if rapid progression is evident. In children with juvenile idiopathic scoliosis and rapid-onset curve progression, severe trunk deformity or pulmonary and/or cardiac compromise can develop. Curves that reach 30° almost always continue to worsen unless treatment is given.3,7 Timely referral to a pediatric spine orthopedist is warranted for children in this age-group.