Bipolar disorders, over time, typically cause fluctuations in mood, activity, and energy level. If disorders go untreated, a patient’s behavior may cause considerable damage to relationships, finances, and reputations. And for some patients, the disorder can take the ultimate toll, resulting in death by suicide or accident.

Subtypes of bipolar disorder differ in the timing and severity of manic (or hypomanic) and depressive symptoms or episodes. Type I is the classic manic-depressive illness; type II is characterized by chronic treatment-resistant depression punctuated by hypomanic episodes; and cyclothymia leads to chronic fluctuations in mood. The diagnostic category “bipolar disorder not otherwise specified” applies to patients who meet some, but not all, of the criteria for other bipolar disorder subtypes.1

Prevalence. As with other mood symptoms or disorders, patients with bipolar disorder are often seen first in primary care due, in part, to barriers to obtaining psychiatric care or to avoidance of the perceived stigma in seeking such care.2 In a systematic review of patients who were interviewed randomly in primary care settings, 0.5% to 4.3% met criteria for bipolar disorder.3 The average age of onset for bipolar disorder is 15 to 19 years.4 In the United States, the prevalence of bipolar disorder type I is 1%; type II is 1.1%.3

The cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but familial predisposition, biopsychosocial factors, and environment all seem to play a role. Children of parents with bipolar disorder have a 4% to 15% chance of receiving the same diagnosis, compared with children of parents without bipolar disorder, whose risk is only as high as 2%.5,6

Clinical presentation varies

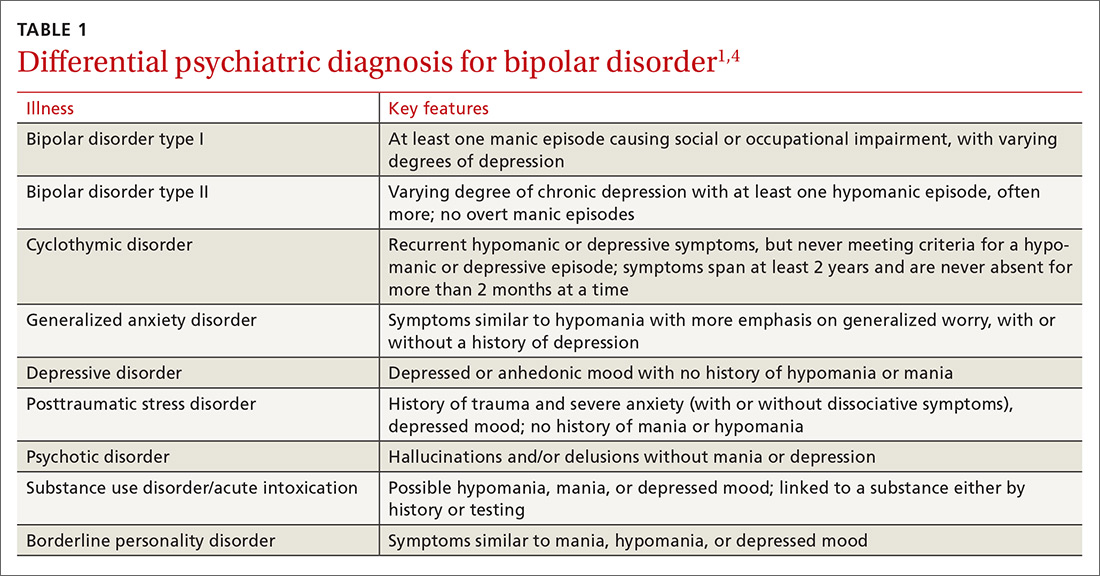

When patients with bipolar disorder are first seen in the office, their state may be depression, mania, hypomania, or even euthymia. Keep in mind that the first 3 aberrations may indicate other disorders, either psychiatric (TABLE 1)1,4 or medical (eg, hyperthyroidism, delirium).

Verify a true depressive episode

Symptoms must last for 2 weeks and include anhedonia or depressed mood, as well as some combination of changes in sleep, increased feelings of guilt, poor concentration, changes in appetite, loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or suicidal thoughts.1

Know the criteria for mania

True mania is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy, and lasting at least one week for most of the day, nearly every day (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary).

During that time, the patient must also exhibit at least 3 or more of the following symptoms (not counting irritability, if present): 1

- distractibility,

- insomnia,

- grandiosity,

- flights of ideas,

- increased goal-directed activity or agitation,

- rapid/pressured speech, or

- reckless behaviors.

How hypomania differs from mania. The symptoms of hypomania are less severe than those of mania—eg, social functioning is less impaired or is even normal, and there is no need for hospitalization. Patients may feel they have been much more productive than usual or have needed less sleep to engage in daily activities. Hypomania may be present but not reported by patients who perceive nothing wrong.1,4