Rule out alternate diagnoses and apply DSM-5 criteria

There are no objective tests to confirm a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. If you suspect bipolar disorder, focus your clinical evaluation on ruling out competing mental health or medical diagnoses, and on determining whether the patient’s history meets criteria for a bipolar disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).1

Explore the patient’s psychiatric history (including hospitalizations, medications, and electroconvulsive therapy), general medical history, family history of psychiatric disorders (including suicide), and social history (including substance use and abuse). And carefully observe mental status. Confirming a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may take multiple visits, but strongly suggestive symptoms could warrant empirical treatment.

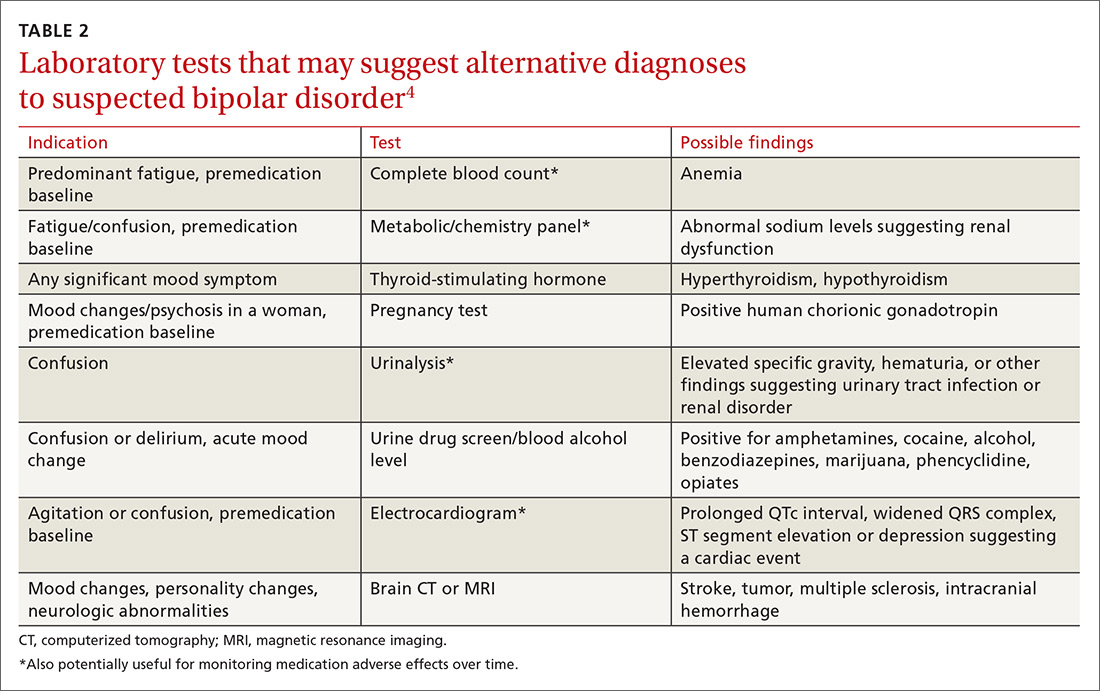

Helpful scales. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218) and the Beck Depression Inventory (http://www.hr.ucdavis.edu/asap/pdf_files/Beck_Depression_Inventory.pdf) are useful for ruling out depressive disorders. Other scales are available, but they cannot confirm bipolar disorder. Laboratory testing selected according to patient symptoms (TABLE 24) can help rule out alternative diagnoses, but are also useful for establishing a baseline for medications.

Pharmacologic treatment: Match agents to symptoms

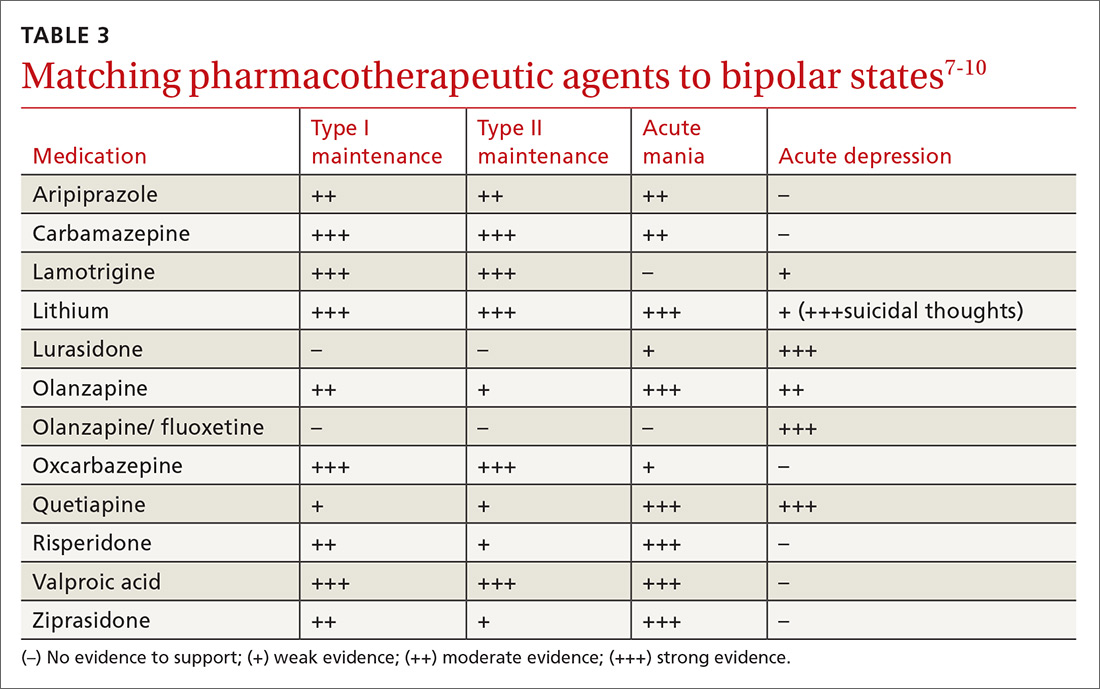

When treating bipolar disorder, choose a drug that targets a patient’s specific symptoms (TABLE 3).7-10 In primary care, the most commonly-used treatments for bipolar disorder type II are lamotrigine, valproic acid, and lithium.11

When to refer

Many cases of bipolar disorder type II can be managed successfully in a primary care practice, as can some cases of stable bipolar disorder type I. Psychiatric consultation may be most beneficial if the patient has recently attempted suicide or has suicidal ideation, has symptoms refractory to treatment, has poor medication adherence, or is misusing medications.

Even when patients are co-managed with psychiatric consultation, family physicians often ensure patients’ medication adherence, help patients understand their illness, manage overall health-related behaviors (including getting sufficient sleep), and make sure patients follow up as needed with their psychiatrist. Often, once patients have achieved equilibrium on mood-stabilizing (or other) medications, you can manage them and monitor medications with further consultation only as needed for clinical deterioration or other issues. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be useful as adjunctive treatment, particularly when patients are in active treatment.12

› CASE

This case is typical for many patients with depressed mood. A few key features in the patient’s history suggest bipolar disorder type II:

- depression that has been refractory to treatment

- multiple failed drug treatments, with mood-related adverse effects

- hypomania perceived as a “productive time,” and not as a problem

- absence of overt manic symptoms.

The patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type II with current depressed mood and no evidence of acute mania. She was started on valproic acid 250 mg po tid. She reported an initial improvement in mood but stopped the medication after one month because it caused intolerable drowsiness. She was then prescribed lamotrigine progressing gradually in 2-week intervals from 25 mg to 100 mg daily. She tolerated the medication well, and after 3 months of treatment, her mood symptoms improved and she had no further episodes of depressed mood.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Jason Wells, MD, Department of Family and Geriatric Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 201 Abraham Flexner Way, Suite 690, Louisville, KY 40202; mjwell04@louisville.edu.