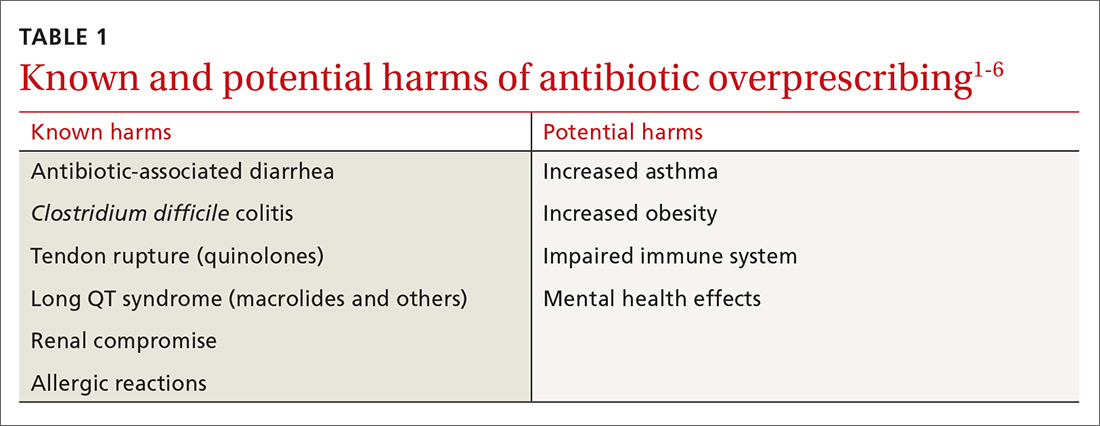

Despite universal agreement that antibiotic overprescribing is a problem, the practice continues to vex us. Antibiotic use—whether appropriate or not—has been linked to rising rates of antimicrobial resistance, disruption of the gut microbiome leading to Clostridium difficile infections, allergic reactions, and increased health care costs (TABLE 11-6). And yet, physicians continue to overprescribe this class of medication.

A 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report estimates that at least 30% of antibiotics prescribed in US outpatient settings are unnecessary.7 Another report cites a slightly higher figure across a variety of health care settings.8 Pair these findings with the fact that there are currently few new drugs in development to target resistant bacteria, and you have the potential for a post-antibiotic era in which common infections could become lethal.7

In 2003, the CDC launched its “Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work” program, focused on decreasing inappropriate antibiotic use in the outpatient setting.9 In 2014, the White House released the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria with a goal of decreasing inappropriate outpatient antibiotic use by 50% and inappropriate inpatient use by 20% by 2020.10 And, on an international level, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a 5-year strategic framework in 2015 for implementing its Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance.11

Family practitioners are on the front lines of this battle. Here’s what we can do now.

When and where are antibiotics most often inappropriately prescribed?

The diagnosis leading to the most frequent inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics is acute respiratory tract infection (ARTI), which includes bronchitis, otitis media, pharyngitis, sinusitis, tonsillitis, the common cold, and pneumonia. Up to 40% of antibiotic prescriptions for these conditions are unnecessary.8,12 Bronchitis is the most common ARTI diagnosis associated with inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions, while sinusitis, suppurative otitis media, and pharyngitis are the diagnoses associated with the lion’s share of all (appropriate and inappropriate) antibiotic prescriptions within the ARTI category.8,9,12,13 There are national clinical guidelines delineating when antibiotic treatment is appropriate for these conditions.14-16

With respect to setting, studies have presented conflicting results as to whether there is a difference between antibiotic prescribing in office-based vs emergency department (ED) settings. Here is a sample of some of the literature to date:

- One study found a higher rate of antibiotic prescribing during ED visits (21%) than office visits (9%), despite the fact that between 2007 and 2009, more antibiotic prescriptions were written for adults in primary care offices than in either outpatient hospital clinics or EDs.17

- A cross-sectional study focused on the frequency with which antibiotics were prescribed for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis. Researchers analyzed data from 2005 to 2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS) and found that more than half of the patients received prescriptions for antibiotics, but that there was no overall difference in antibiotic prescriptions between primary care and ED presentation.18

- A retrospective analysis that examined antibiotic prescribing found that between 2006 and 2010, outpatient hospital practices (56%) and community-practice offices (60%) prescribed more antibiotics for ARTIs than EDs (51%).12

Stick to narrow-spectrum agents when possible

Using broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as quinolones or imipenem, first line, contributes more to the problem of antibiotic resistance than does prescribing narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin, cephalexin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.7 Yet between 2007 and 2009, broad-spectrum agents were prescribed for 61% of outpatient adult visits in which patients received an antibiotic prescription.17 Quinolones (25%), macrolides (20%), and aminopenicillins (12%) were most commonly prescribed, and antibiotic prescriptions were most often written for respiratory conditions, such as bronchitis, for which we now know antibiotics are rarely indicated.17

Between 2006 and 2008, pediatric patients who received antibiotic prescriptions were given broad-spectrum agents 50% of the time, of which macrolides were the class most commonly prescribed.13

More recently, researchers examined the frequency with which physicians prescribe narrow-spectrum, first-line antibiotics for otitis media, sinusitis, and pharyngitis using 2010 to 2011 NAMCS/NHAMCS data. They found that physicians used first-line agents recommended by professional guidelines 52% of the time, although it was estimated that they would have been appropriate in 80% of cases; pediatric patients were more likely to receive appropriate first-line antibiotics than adult patients.19 Macrolides, especially azithromycin, were the most common non–first-line antibiotics prescribed.19,20 The bottom line is that when antibiotics are indicated for upper respiratory infections (otitis media, sinusitis, and pharyngitis), physicians should prescribe a narrow-spectrum antibiotic first.

Antibiotic overprescribing affects the gut and beyond

The human intestinal microbiome is composed of a diverse array of bacteria, viruses, and parasites.21 The main functions of the gut microbiome include interacting with the immune system and participating in biochemical reactions in the gut, such as absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and the production of vitamin K.