As we know, antibiotics decrease the diversity of gut bacteria, which, in turn, can cause less efficient nutrient extraction, as well as a vulnerability to enteric infections.21 It is well known, for example, that the bacterial gut microbiome can either inhibit or promote diarrheal illnesses such as those caused by C. difficile. C. difficile infection (CDI) is now the most common health care-related infection, accounting for approximately a half million health care facility infections a year.22 CDI extends hospital stays an average of almost 10 days and is estimated to cost the health care system $6.3 billion annually.23

Antibiotics can also eliminate antibiotic-susceptible organisms, allowing resistant organisms to proliferate.4 They also promote the transmission of genes for antibiotic resistance between gut bacteria.4

Beyond the gut

Less well known is that gut bacteria can promote or inhibit extraintestinal infections.

Gut bacteria and HIV. In early human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, for example, gut populations of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria are reduced, and the gut barrier becomes compromised.24 Increasing translocation of bacterial products is associated with HIV disease progression. Preservation of Lactobacillus populations in the gut is associated with markers predictive of better HIV outcomes, including a higher CD4 count, a lower viral load, and less evidence of gut microbial translocation.24 This underscores the importance of maintaining a healthy gut flora in patients with HIV, using such steps as avoiding unnecessary antibiotics.

Gut bacteria and stress, depression. Antibiotics directly induce the expression of key genes that affect the stress response.25 While causative studies are lacking, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that the gut microbiome is involved in 2-way communication with the brain and can affect, and be affected by, stress and depression.21,26-30 Diseases and conditions that seem to have a putative connection to a disordered microbiome (dysbiosis) include depression, anxiety, Crohn’s disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.

Gut bacteria and childhood obesity. Repeated use of broader-spectrum antibiotics in children <24 months of age increases the risk of developing childhood obesity.1,6 One theory for the association is that the effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on the intestinal flora of young children may alter long-term energy homeostasis resulting in a higher risk for obesity.1

Gut bacteria and asthma. Studies demonstrate differences in the gut microbiome of asthmatic and nonasthmatic patients. These differences affect the activities of helper T-cell subsets (Th1 and Th2), which in turn affect the development of immune tolerance.31

Although additional studies are needed to confirm these findings, the evidence collected thus far should make us all pause before prescribing drugs that can alter our microbiome in complex and only partially understood ways.

What can we do right now?

The issues created by the inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics have been known for decades, and multiple attempts have been made to find solutions and implement change. Although some small successes have occurred, little overall progress has been made in reducing antibiotic prescribing in the general population. A historical review of why physicians prescribe antibiotics inappropriately and the interventions that have successfully reduced this prescribing may prove valuable as we continue to look for new, effective answers.

Why do we overprescribe antibiotics? A 2015 systematic literature review found that patient demand, pharmaceutical company marketing activities, limited up-to-date information sources, and physician fear of losing their patients are major reasons physicians cite for prescribing antibiotics.32

In a separate study that explored antibiotic prescribing habits for acute bronchitis,33 clinicians cited “patient demand” as the major reason for prescribing antibiotics. Respondents also reported that “other physicians were responsible for inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.”33

Strategies that work

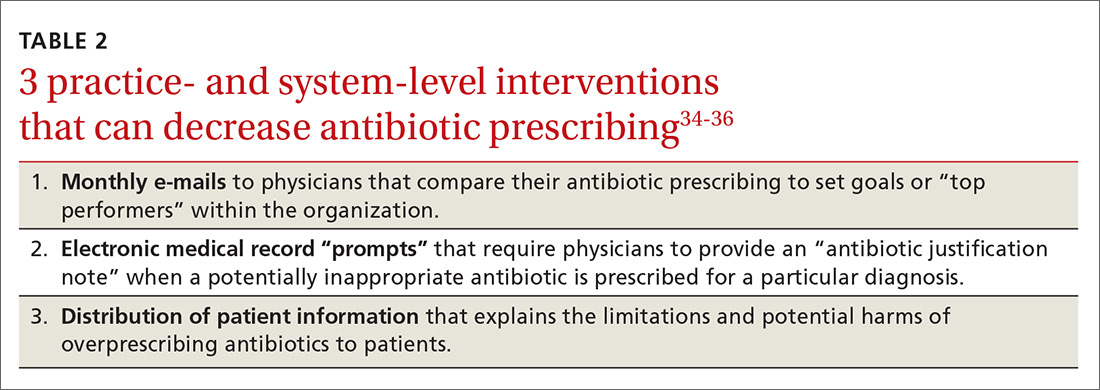

Some early intervention programs directed at reducing antibiotic prescribing demonstrated success (TABLE 2).34-36 One example comes from a 1996 to 1998 study of 4 primary care practices.34 Researchers evaluated the impact of a multidimensional intervention effort targeted at clinicians and patients and aimed at lowering the use of antimicrobial agents for acute uncomplicated bronchitis in adults. It incorporated a number of elements, including office-based and household patient educational materials, and a clinician intervention involving education, practice profiling, and academic detailing. Physicians in this program reduced their rates of antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated bronchitis from 74% to 48%.34

Employing EMRs. A more recent study focused on using electronic medical records (EMRs) and communications to modify physician antibiotic prescribing.35 By sending physicians monthly emails comparing their prescribing patterns to peers and “typical top performers,” inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for ARTIs went from 19.9% to 3.7%.35

In another effort, the same researchers modified physicians’ EMRs to detect when potentially inappropriate antibiotics were prescribed. The system then prompted the physician to provide an “antibiotic justification note,” which remained visible in the patient’s chart. This approach, which encouraged physicians to follow prescribing guidelines by taking advantage of their concerns about their reputations, produced a 77% reduction in antibiotic prescribing.35

Focusing on the public. Studies have also examined the effectiveness of educating the public about when antibiotics are not likely to be helpful and of the harms of unnecessary antibiotics. Studies conducted in Tennessee and Wisconsin that combined prescriber and community education about unnecessary antibiotics for children found that the intervention reduced antibiotic prescribing in both locations by about 19% compared with about a 9% reduction in the control groups.36,37