- Control blood pressure to at least 150/80 mm Hg or lower to reduce mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes (A). Strongly consider the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor to reduce the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) and total mortality (A).

- In obese patients with type 2 diabetes, consider the use of metformin, unless contraindicated (A).

- Consider the use of a statin for patients with diabetes, even when their cholesterol level is normal (A).

- Screen patients with type 2 diabetes for peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease to reduce the risk of major amputation (B).

Diabetes need not automatically sentence patients to the well-known ravages of the disease. Evidence-supported preventive strategies can forestall complications.

Increasing evidence suggests diabetes can be prevented by a combination of lifestyle changes and medications. Key interventions for patients with established type 2 diabetes include tight control of blood glucose levels, reduction of blood pressure and lipid levels, and early identification of diabetes-related neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy. Antiplatelet therapy may also be beneficial.

Primary prevention: should intervention begin with prediabetes states?

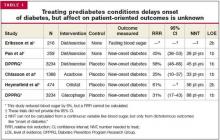

Treatment of risk factors for diabetes (eg, obesity) and management of prediabetes (eg, impaired glucose tolerance) has suggested early intervention can forestall the development of type 2 diabetes (Table 1). Three trials addressed intensive lifestyle/diet modification. Though the onset of clinically diagnosed diabetes was delayed while patients adhered to these strategies, long-term studies of lifestylemodification have not been performed.1–3

Several other investigations have looked at whether prescription medications achieve similar benefit. Metformin,3 acarbose,4 and orlistat5 have been studied in populations with prediabetes. These interventions appear to delay the onset of diabetes (number needed to treat [NNT]=33–88 patient-years) and to reduce blood sugar levels by 5% to 10%. A post-hoc analysis of the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) trial6 also suggests a favorable effect with the ACE inhibitor, ramipril (NNT=250 patient-years). However, patient-oriented outcomes—development of microvascular or macrovascular disease—were not assessed in these trials. Consequently, the ultimate benefit of treating prediabetes states remains uncertain.

SECONDARY PREVENTION: DOES EARLY DETECTION OF DIABETES HELP DELAY COMPLICATIONS?

No randomized trial of screening has reported any patient-oriented benefits. However, based on consensus opinion, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends screening every person aged 45 years and older every 3 years (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).7 The characteristics of a clinically recognized disease like diabetes, however, may differ significantly from the characteristics of the subclinical states that would be recognized with screening. Therefore, though the US Preventive Health Services Task Force8 has concluded there is no evidence to recommend screening average risk individuals for diabetes, it does recommend screening individuals at increased risk of macrovascular changes (eg, those with hypertension) (SOR: B). This is based in part on indirect evidence that tighter blood pressure targets may be beneficial for patients with diabetes. (See the Clinical Inquiry, “Does screening for diabetes in at-risk patients improve long-term outcomes?”)

Tertiary prevention: preventing complications of existing diabetes

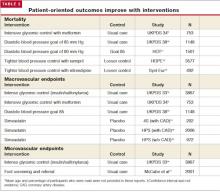

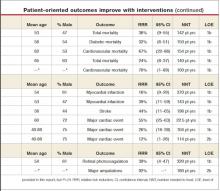

Patient-oriented outcomes in diabetes can be significantly improved with numerous interventions (Table 2).

Tight glycemic control warranted

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study14 (UKPDS) randomized participants to usual diabetic care or intensive glycemic control with insulin or sulfonylureas over 10 years. Intensive control reduced average hemoglobin A1c from 7.9% to 7.0%; it also reduced aggregate microvascular complications, mainly a relative 39% decreased need for photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy (NNT=320 patient-years). No other individual endpoint was independently affected.

The UKPDS suggested a trend toward 16% fewer relative MIs in the intensive control group; however, the results did not reach statistical significance (P=.052). In addition an increase in major hypoglycemic episodes was noted, worse with insulin than sulfonylureas (relative risk [RR]=257%; number needed to harm [NNH]=1110 patient-years).

Approach to obese patients. The UKPDS also studied intensive control with metformin among a subgroup of obese patients with diabetes (>120% ideal body weight).9 Metformin lowered average hemoglobin A1c only from 8.0% to 7.4%, but reduced relative total mortality by 36% (NNT=142 patient-years). Metformin also reduced the relative chance of MI by 39% (NNT=143 patient-years).

These benefits were reversed, however, in a separate UKPDS subgroup placed first on a sulfonylurea, then receiving metformin if glycemic control was inadequate. Total mortality was relatively increased by 60% (NNH=89 patient-years).9 This adverse outcome disappeared when adjustment was made for age, sex, ethnic group, and glycemic control.

Other potential risks of metformin include lactic acidosis, but 1 recent systematic review found no associated cases of this condition with metformin prescribed in published studies.17

Applying the evidence. Initial treatment of patients with diabetes over 120% of ideal body weight should include tight glucose control with metformin, unless contraindicated (SOR: A). For leaner patients, therapy with a sulfonylurea or insulin is supported by evidence (SOR: B).