Prostate cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world and the second most common cancer among American men, surpassed only by nonmelanoma skin cancer. Prostate cancer led to approximately 28,660 deaths in 2008 (the second leading cause of cancer deaths that year), and 192,000 new cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed in 2009.1-7

The incidence of prostate cancer has been rising about 1% annually since 1995.4 Explanations for the increasing incidence, though not certain, are believed to be both genetic and environmental. In the US, prostate cancer–associated morbidity and mortality rates are highest in African-American men.8 Men of African and Caribbean descent are at three times the risk for prostate cancer, compared with white men.9

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing has nearly doubled the chance that a man will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in his lifetime. Prior to widespread use of PSA testing, a white man had a one-in-eleven chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer in his lifetime; currently, that man’s chances are one in six.6

The incidence of prostate cancer increases as men age, with those in their 40s accounting for less than 1% of prostate cancer cases, compared with men older than 65, who account for more than 75% of cases.10 Besides age, other risk factors include a positive family history of prostate cancer in the father or brother(s) and African-American ethnicity.2,3

No clear link has been demonstrated between diet and prostate cancer. Tobacco use is not currently considered a risk factor for prostate cancer, but pooled data from 24 cohort studies enrolling more than 26,000 participants with prostate cancer revealed a 9% to 30% increase in both incident and fatal prostate cancer among men who smoked.3

ANATOMY AND FUNCTION

The prostate gland sits under the bladder and surrounds the urethra; in a young man, it is approximately the size of a walnut. As a man ages, the prostate begins to enlarge. Once a man reaches his 50s, he may begin to experience lower urinary tract symptoms11,12 (see Table 111,12).

The prostate produces fluid containing prostate-specific antigen, a type of protein that helps liquefy the semen and facilitate sperm motility. PSA is a component of the seminal fluid that is necessary for ejaculation. The prostate and the seminal vessels contract during ejaculation, expelling fluid through the prostate’s ejaculatory ducts and out along the urethra.10 PSA levels in the serum are normally very low. Prostatic disease, inflammation, or trauma can lead to increased levels of PSA in the serum. Elevated serum PSA has become an important marker of many prostate diseases, including benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, and prostate cancer13—the focus of this article.

The prostate gland is comprised of three zones: central, transitional, and peripheral. The peripheral zone, located at the back of the prostate, is the most susceptible to cancer. Prostate cancer is typically adenocarcinoma.14

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

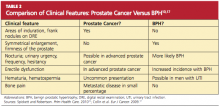

As a result of widespread screening of serum PSA, prostate cancer is often diagnosed before symptoms develop or a palpable nodule appears.5,15,16 Prostate cancer not identified through PSA screening is typically detected either by digital rectal examination (DRE) or in an investigation of genitourinary symptoms. For men who are symptomatic, the primary care provider can order a urine test to rule out infection (which can raise the PSA level), order PSA screening, and perform a DRE, which can also help to rule out benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH)17 (see Table 210,17).

PSA TESTING

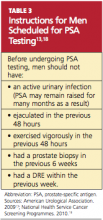

Primary care providers can make an important contribution to men’s health by educating those older than 50 regarding the pros and cons of PSA testing. It has been found that 47% of men between ages 50 and 70 have no knowledge of the PSA test. Men in the upper socioeconomic groups are more likely to be aware of the test.10 Patients scheduled to undergo PSA testing should be advised in advance to avoid certain activities and circumstances (see Table 3,13,18).

Screening serum PSA can reduce the number of prostate cancer–associated deaths by 31%, but this benefit must be weighed against a degree of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.2,5,6,16,19 Although the incidence of prostate cancer is 16%, only 2% of affected men will succumb to the disease.16 Up to 30% of prostate cancers detected by PSA may have otherwise remained clinically silent throughout the patient’s life.19

Additionally, PSA screening rates remain high in men between ages 75 and 80, who may be at risk for screening that is unnecessary due to an increase in competing causes of death.19 In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging,19,20 a longitudinal cohort study in which 849 men were enrolled, researchers measured the proportion of men, by PSA and age, who died of prostate cancer or in whom aggressive prostate cancer developed. It was found that no participants between ages 75 and 80 with a PSA below 3.0 ng/mL died of prostate cancer, but men of all ages with a PSA greater than 3.0 ng/mL had a continually increasing probability of death from prostate cancer. These findings suggest that it may be safe to discontinue PSA testing in men older than 75 whose PSA level is lower than 3.0 ng/mL.19