The Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study in Australia and New Zealand1 examined the optimal time to initiate dialysis. This well-designed, randomized, controlled trial gave the nephrology community guidelines for treating patients as they progress through chronic kidney disease to stage 5 (CKD 5). The IDEAL investigators demonstrated that planned early initiation of dialysis did not enhance survival—and in some cases, it hastened death.1

Although most patients have a nephrology provider by the time they reach CKD 5 (ie, kidney failure), primary care providers can be instrumental in preparing the patient for what lies ahead as kidney failure progresses. Presented here is an overview of diagnosis and management of the patient with CKD 5 in the 21st century.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old woman with an extensive history of diabetes and hypertension presents to her primary care clinician complaining of a lack of energy. She has just returned from a trip to Disney World, where she says she was unable to keep up with her grandchildren. She sat in the shade while they enjoyed Space Mountain and other attractions, and because of uncustomary fatigue, she required a nap every afternoon.

Physical examination shows an elderly female in no acute distress. Cardiac exam shows a regular heart rate and rhythm, the patient’s lungs are clear, and she has 1+ pitting leg edema bilaterally. The patient’s blood pressure is slightly elevated at 142/92 mm Hg, and no protein is detected on spot urine testing.

Blood work is ordered, including a complete blood count, a comprehensive metabolic panel, and an A1C. Results include a hemoglobin level of 8.7 g/dL (reference range for women, 12.0 to 16.0 g/dL), a serum creatinine level (SCr) of 3 mg/dL (range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], 15 mL/min/1.73 m2), and an A1C value of 7.5% (normal, & < 7%).

The patient is told that she is in kidney failure and is referred immediately to a nephrology practice, where she is seen the following day. After her appointment, she returns to the primary care office. When she is asked when she will be starting dialysis, she seems surprised, saying, “They told me I was doing well. I need some shots for my blood, but they didn’t seem worried at all.”

Is this patient being managed correctly by the nephrology practitioner?

EPIDEMIOLOGY

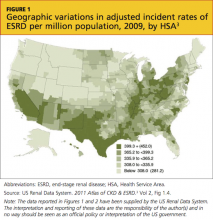

Presently, more than 1 million persons in the United States have CKD 5, and 500,000 are undergoing dialysis. The number of patients with CDK 5 who are on dialysis has doubled since 1994 and is projected to reach 774,000 by 20202,3 (see Figure 13 and Figure 23).

CKD 5 is defined as an eGFR below 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study group formula; or as a creatinine clearance of less than 15 mL/min, using the Cockcroft-Gault formula.4-6 Both formulas have limitations, since they are not fully accurate at extremes of age, with variations in weight, for some racial mixes, or for the very malnourished patient.7,8 However, they do correct for normal age-related loss of kidney function, gender, and SCr, and they are currently the generally accepted formulas.4

A rise in SCr is exponential; for each doubling of the SCr, a reduction in kidney function of approximately 50% occurs. This means that a rise in SCr from 4 to 8 mg/dL is equivalent (in the proportion of loss of kidney function) to a rise of SCr from 0.5 to 1 mg/dL. Commonly, patients are not referred to nephrology until the SCr doubles to 4 or 6 mg/dL—whereas the rise in SCr from 0.5 to 1 mg/dL should be of greatest concern to the primary care provider, prompting a referral.9 Early recognition of reduced renal function allows for identification of potentially reversible etiologies and the slowing of CKD progression.

INDICATIONS FOR RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY

Not all patients with an eGFR below 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 are started on dialysis immediately. The decision to initiate dialysis is guided by assessment of a constellation of uremic manifestations—not eGFR alone. Newer data suggest that early initiation of dialysis may be associated with increased mortality.10-15

The IDEAL study,1 a well-designed, randomized, controlled trial of all patients who started dialysis in Australia and New Zealand over a multiyear period, was designed to determine the optimal time to initiate dialysis. Patients were randomized to start dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) at an eGFR between 10 and 14 mL/min/1.73 m2 or between 5 and 7 mL/min/1.73 m2. While there was some overlap and some patients were started on dialysis outside their randomized eGFR (eg, earlier than the allotted time because symptoms developed), what the IDEAL investigators found surprised the entire nephrology community: Early dialysis starts did not enhance survival and, in some cases, it hastened death.1